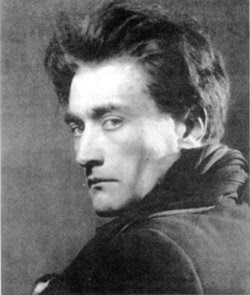

Artaud in The Passion of Joan of Arc

Oriental and Occidental Theater

The Balinese theater has revealed to us a physical and non¬verbal idea of the theater, in which the theater is contained within the limits of everything that can happen on a stage, independently of the written text, whereas the theater as we conceive it in the Occident has declared its alliance with the text and finds itself limited by it. For the Occidental theater the Word is everything, and there is no possibility of expression without it; the theater is a branch of literature, a kind of sonorous species of language, and even if we admit a differ¬ence between the text spoken on the stage and the text read by the eyes, if we restrict theater to what happens between cues, we have still not managed to separate it from the idea of a performed text.

This idea of the supremacy of speech in the theater is so deeply rooted in us, and the theater seems to such a degree merely the material reflection of the text, that everything in the theater that exceeds this text, that is not kept within its limits and strictly conditioned by it, seems to us purely a mat¬ter of mise en scene, and quite inferior in comparison with the text.

Presented with this subordination of theater to speech, one might indeed wonder whether the theater by any chance possesses its own language, whether it is entirely fanciful to consider it as an independent and autonomous art, of the same rank as music, painting, dance, etc. . . .

One finds in any case that this language, if it exists, is nec¬essarily identified with the mise en scene considered:

1. as the visual and plastic materialization of speech,

2. as the language of everything that can be said and signi¬fied upon a stage independently of speech, everything that finds its expression in space, or that can be affected or disintegrated by it.

Once we regard this language of the mise en scene as the pure theatrical language, we must discover whether it can attain the same internal ends as speech, whether theatrically and from the point of view of the mind it can claim the same intellectual efficacy as the spoken language. One can wonder, in other words, whether it has the power, not to define thoughts but to cause thinking, whether it may not entice the mind to take profound and efficacious attitudes toward it from its own point of view.

In a word, to raise the question of the intellectual efficacy of expression by means of objective forms, of the intellectual efficacy of a language which would use only shapes, or noise, or gesture, is to raise the question of the intellectual efficacy of art.

If we have come to attribute to art nothing more than the values of pleasure and relaxation and constrain it to a purely formal use of forms within the harmony of certain external -relations, that in no way spoils its profound expressive value; but the spiritual infirmity of the Occident, which is the place par excellence where men have confused art and aestheticism, is to think that its painting would function only as painting, dance which would be merely plastic, as if in an attempt to castrate the forms of art, to sever their ties with all the mystic attitudes they might acquire in confrontation with the absolute.

One therefore understands that the theater, to the very degree that it remains confined within its own language and in correlation with it, must break with actuality. Its object is not to resolve social or psychological conflicts, to serve as battlefield for moral passions, but to express objectively cer¬tain secret truths, to bring into the light of day by means of active gestures certain aspects of truth that have been buried under forms in their encounters with Becoming.

To do that, to link the theater to the expressive possibilities of forms, to everything in the domain of gestures, noises, colors, movements, etc., is to restore it to its original direction, to reinstate it in its religious and metaphysical aspect, is to reconcile it with the universe.

But words, it will be said, have metaphysical powers; it is not forbidden to conceive of speech as well as of gestures on the universal level, and it is on that level moreover that speech acquires its major efficacy, like a dissociative force exerted upon physical appearances, and upon all states in which the mind feels stabilized and tends towards repose. And we can readily answer that this metaphysical way of considering speech is not that of the Occidental theater, which employs speech not as an active force springing out of the destruction of appearances in order to reach the mind itself, but on the contrary as a completed stage of thought which is lost at the moment of its own exteriorization.

Speech in the Occidental theater is used only to express psychological conflicts particular to man and the daily reality of his life. His conflicts are clearly accessible to spoken lan¬guage, and whether they remain in the psychological sphere or leave it to enter the social sphere, the interest of the drama will still remain a moral one according to the way in which its conflicts attack and disintegrate the characters. And it will indeed always be a matter of a domain in which the verbal solutions of speech will retain their advantage. But these moral conflicts by their very nature have no absolute need of the stage to be resolved. To cause spoken language or expression by words to dominate on the stage the objective expression of gestures and of everything which affects the mind by sensuous and spatial means is to turn one's back on the physical neces¬sities of the stage and to rebel against its possibilities.

It must be said that the domain of the theater is not psycho¬logical but plastic and physical. And it is not a question of whether the physical language of theater is capable of achiev¬ing the same psychological resolutions as the language of words, whether it is able to express feelings and passions as well as words, but whether there are not attitudes in the realm of thought and intelligence that words are incapable of grasp¬ing and that gestures and everything partaking of a spatial language attain with more precision than they.

Before giving an example of the relations between the phy¬sical world and the deepest states of mind, let me quote what I have written elsewhere:

"All true feeling is in reality untranslatable. To express it is to betray it. But to translate it is to dissimulate it. True ex¬pression hides what it makes manifest. It sets the mind in opposition to the real void of nature by creating in reaction a kind of fullness in thought. Or, in other terms, in relation to the manifestation-illusion of nature it creates a void in thought. All powerful feeling produces in us the idea of the void. And the lucid language which obstructs the appearance of this void also obstructs the appearance of poetry in thought. That is why an image, an allegory, a figure that masks what it would reveal have more significance for the spirit than the lucidities of speech and its analytics.

"This is why true beauty never strikes us directly. The setting sun is beautiful because of all it makes us lose."

The nightmares of Flemish painting strike us by the juxta¬position with the real world of what is only a caricature of that world; they offer the specters we encounter in our dreams. They originate in those half-dreaming states that produce clumsy, ambiguous gestures and embarrassing slips of the tongue: beside a forgotten child they place a leaping harp; near a human embryo swimming in underground waterfalls they show an army's advance against a redoubtable fortress. Be¬side the imaginary uncertainty the march of certitude, and beyond a yellow subterranean light the orange flash of a great autumn sun just about to set.

It is not a matter of suppressing speech in the theater but of changing its role, and especially of reducing its position, of considering it as something else than a means of conducting human characters to their external ends, since the theater is concerned only with the way feelings and passions conflict with one another, and man with man, in life.

To change the role of speech in theater is to make use of it in a concrete and spatial sense, combining it with everything in the theater that is spatial and significant in the concrete domain;—to manipulate it like a solid object, one which overturns and disturbs things, in the air first of all, then in an infinitely more mysterious and secret domain but one that admits of extension, and it will not be very difficult to identify this secret but extended domain with that of formal anarchy on the one hand but also with that of continuous formal crea¬tion on the other.

This is why the identification of the theater's purpose with every possibility of formal and extended manifestation gives rise to the idea of a certain poetry in space which itself is taken for sorcery.

In the Oriental theater of metaphysical tendency, contrasted to the Occidental theater of psychological tendency, forms assume and extend their sense and their significations on all possible levels; or, if you will, they set up vibrations not on a single level, but on every level of the mind at once.

And it is because of the multiplicity of their aspects that they can disturb and charm and continuously excite the mind. It is because the Oriental theater does not deal with the external aspects of things on a single level nor rest content with the simple obstacle or with the impact of these aspects on the senses, but instead considers the degree of mental possibil¬ity from which they issue, that it participates in the intense poetry of nature and preserves its magic relations with all the objective degrees of universal magnetism.

It is in the light of magic and sorcery that the mise en scene must be considered, not as the reflection of a writtten text, the mere projection of physical doubles that is derived from the written work, but as the burning projection of all the objective consequences of a gesture, word, sound, music, and their com¬binations. This active projection can be made only upon the stage and its consequences found in the presence of and upon the stage; and the author who uses written words only has nothing to do with the theater and must give way to specialists in its objective and animated sorcery.

No More Masterpieces

One of the reasons for the asphyxiating atmosphere in which we live without possible escape or remedy—and in which we all share, even the most revolutionary among us—is our re¬spect for what has been written, formulated, or painted, what has been given form, as if all expression were not at last ex¬hausted, were not at a point where things must break apart if they are to start anew and begin fresh.

We must have done with this idea of masterpieces reserved for a self-styled elite and not understood by the general public; the mind has no such restricted districts as those so often used for clandestine sexual encounters.

Masterpieces of the past are good for the past: they are not good for us. We have the right to say what has been said and even what has not been said in a way that belongs to us, a way that is immediate and direct, corresponding to present modes of feeling, and understandable to everyone.

It is idiotic to reproach the masses for having no sense of the sublime, when the sublime is confused with one or another of its formal manifestations, which are moreover always de¬funct manifestations. And if for example a contemporary pub¬lic does not understand Oedipus Rex, I shall make bold to say that it is the fault of Oedipus Rex and not of the public.

In Oedipus Rex there is the theme of incest and the idea that nature mocks at morality and that there are certain unspecified powers at large which we would do well to beware of, call them destiny or anything you choose.

There is in addition the presence of a plague epidemic which is a physical incarnation of these powers. But the whole in a manner and language that have lost all touch with the rude and epileptic rhythm of our time. Sophocles speaks grandly perhaps, but in a style that is no longer timely. His language is too refined for this age, it is as if he were speaking beside the point.

However, a public that shudders at train wrecks, that is familiar with earthquakes, plagues, revolutions, wars; that is sensitive to the disordered anguish of love, can be affected by all these grand notions and asks only to become aware of them, but on condition that it is addressed in its own language, and that its knowledge of these things does not come to it through adulterated trappings and speech that belong to extinct eras which will never live again.

Today as yesterday, the public is greedy for mystery: it asks only to become aware of the laws according to which destiny manifests itself, and to divine perhaps the secret of its appari¬tions.

Let us leave textual criticism to graduate students, formal criticism to esthetes, and recognize that what has been said is not still to be said; that an expression does not have the same value twice, does not live two lives; that all words, once spoken, are dead and function only at the moment when they are uttered, that a form, once it has served, cannot be used again and asks only to be replaced by another, and that the theater is the only place in the world where a gesture, once made, can never be made the same way twice.

If the public does not frequent our literary masterpieces, it is because those masterpieces are literary, that is to say, fixed; and fixed in forms that no longer respond to the needs of the time.

Far from blaming the public, we ought to blame the formal screen we interpose between ourselves and the public, and this new form of idolatry, the idolatry of fixed masterpieces which is one of the aspects of bourgeois conformism.

This conformism makes us confuse sublimity, ideas, and things with the forms they have taken in time and in our minds—in our snobbish, precious, aesthetic mentalities which the public does not understand.

How pointless in such matters to accuse the public of bad taste because it relishes insanities, so long as the public is not shown a valid spectacle; and I defy anyone to show me here a spectacle valid—valid in the supreme sense of the theater— since the last great romantic melodramas, i.e., since a hundred years ago.

The public, which takes the false for the true, has the sense of the true and always responds to it when it is manifested. However it is not upon the stage that the true is to be sought nowadays, but in the street; and if the crowd in the street is offered an occasion to show its human dignity, it will always do so.

If people are out of the habit of going to the theater, if we have all finally come to think of theater as an inferior art, a means of popular distraction, and to use it as an outlet for our worst instincts, it is because we have learned too well what the theater has been, namely, falsehood and illusion. It is be¬cause we have been accustomed for four hundred years, that is since the Renaissance, to a purely descriptive and narrative theater—story telling psychology; it is because every possible ingenuity has been exerted in bringing to life on the stage plausible but detached beings, with the spectacle on one side, the public on the other—and because the public is no longer shown anything but the mirror of itself.

Shakespeare himself is responsible for this aberration and decline, this disinterested idea of the theater which wishes a theatrical performance to leave the public intact, without setting off one image that will shake the organism to its foundations and leave an ineffaceable scar.

If, in Shakespeare, a man is sometimes preoccupied with what transcends him, it is always in order to determine the ultimate consequences of this preoccupation within him, i.e., psychology.

Psychology, which works relentlessly to reduce the un¬known to the known, to the quotidian and the ordinary, is the cause of the theater's abasement and its fearful loss of energy, which seems to me to have reached its lowest point. And I think both the theater and we ourselves have had enough of psychology.

I believe furthermore that we can all agree on this matter sufficiently so that there is no need to descend to the repug¬nant level of the modern and French theater to condemn the theater of psychology.

Stories about money, worry over money, social careerism, the pangs of love unspoiled by altruism, sexuality sugar-coated with an eroticism that has lost its mystery have nothing to do with the theater, even if they do belong to psychology. These torments, seductions, and lusts before which we are nothing but Peeping Toms gratifying our cravings, tend to go bad, and their rot turns to revolution: we must take this into account.

But this is not our most serious concern.

If Shakespeare and his imitators have gradually insinuated the idea of art for art's sake, with art on one side and life on the other, we can rest on this feeble and lazy idea only as long as the life outside endures. But there are too many signs that everything that used to sustain our lives no longer does so, that we are all mad, desperate, and sick. And I call for us to react.

This idea of a detached art, of poetry as a charm which exists only to distract our leisure, is a decadent idea and an unmistakable symptom of our power to castrate. . . .

The Theatre of Cruelty - First Manifesto

We cannot continue to prostitute the idea of theatre whose only value lies in its agonizing, magic relationship to reality and danger.

Put in this way, the problem of theatre must arouse universal attention, it being understood that theatre, through its physical aspect and because it requires spatial expression (the only real one in fact) allows the sum total of the magic means in the arts and words to be organically active like renewed exorcisms. From the aforementioned it becomes apparent that theatre will never recover its own specific powers of action until it has also recovered its own language.

That is, instead of harking back to texts regarded as sacred and definitive, we must first break theatre's subjection to the text and rediscover the idea of a kind of unique language somewhere between gesture and thought. [. . .]

TECHNIQUE

The problem is to turn theatre into a function in the proper sense of the word, something as exactly localized as the circulation of our blood through our veins, or the apparently chaotic evolution of dream images in the mind, by an effective mix, truly enslaving our attention.

Theatre will never be itself again, that is to say will never be able to form truly illusive means, unless it provides the audience with truthful distillations of dreams where its taste for crime, its erotic obsessions, its savageness, its fantasies, its Utopian sense of life and objects, even its cannibalism, do not gush out on an illusory make-believe, but on an inner level.

In other words, theatre ought to pursue a re-examination not only of all aspects of an objective, descriptive outside world but also all aspects of an inner world, that is to say man viewed meta¬physically, by every means at its disposal. We believe that only in this way will we be able to talk about imagination's rights in the theatre once more. Neither Humur, Poetry nor Imagination mean anything unless they re-examine man organically through anarchic destruction, his ideas on reality and his poetic vision in reality, generating stupendous flights of form constituting the whole show.

But to view theatre as a second-hand psychological or moral operation and to believe dreams themselves only serve as a substitute is to restrict both dreams' and theatre's deep poetic range. If theatre is as bloody and as inhuman as dreams, the reason for this is that it perpetuates the metaphysical notions in some Fables in a present-day, tangible manner, whose atrocity and energy are enough to prove their origins and intentions in funda¬mental first principles rather than to reveal and unforgettably tie down the idea of continual conflict within us, where life is continually lacerated, where everything in creation rises up and attacks our condition as created beings.

This being so, we can see that by its proximity to the first principles poetically infusing it with energy, this naked theatre language, a non-virtual but real language using man's nervous magnetism, must allow us to transgress the ordinary limits of art and words, actively, that is to say, magically, to produce a kind of total creation in real terms, where man must reassume his position between dreams and events.

SUBJECTS

We do not mean to bore the audience to death with transcendental cosmic preoccupations. Audiences are not interested whether there are profound clues to the show's thought and action, since in general this does not concern them. But these must still be there and that concerns us.

The Show: Every show will contain physical, objective elements per¬ceptible to all. Shouts, groans, apparitions, surprise, dramatic moments of all kinds, the magic beauty of the costumes modelled on certain ritualistic patterns, brilliant lighting, vocal, incantational beauty, attractive harmonies, rare musical notes, colours of objects, the physical rhythm of the moves whose build and fall will be wedded to the beat of moves familiar to all, the tangible appearance of new, surprising objects, masks, puppets many feet high, abrupt lighting changes, the physical action of lighting stimulating heat and cold, and so on.

Staging: This archetypal theatre language will be formed around staging not simply viewed as one degree of refraction of the script on stage, but as the starting point for theatrical creation. And the old duality between author and director will disappear, to be replaced by a kind of single Creator using and handling this language, responsible both for the play and the action.

Stage Language: We do not intend to do away with dialogue, but to give words something of the significance they have in dreams.

Moreover we must find new ways of recording this language, whether these ways are similar to musical notation or to some kind of code.

As to ordinary objects, or even the human body, raised to the dignity of signs, we can obviously take our inspiration from hieroglyphic characters not only to transcribe these signs legibly so they can be reproduced at will, but to compose exact symbols on stage that are immediately legible.

Then again, this coding and musical notation will be valuable as a means of vocal transcription.

Since the basis of this language is to initiate a special use of inflections, these must take up a kind of balanced harmony, a subsidiary exaggeration of speech able to be reproduced at will.

Similarly the thousand and one facial expressions caught in the form of masks can be listed and labeled so they may directly and symbolically participate in this tangible stage language, independently of their particular psychological use.

Furthermore, these symbolic gestures, masks, postures, individual or group moves, whose countless meanings constitute an important part of the tangible stage language of evocative gestures, emotive arbitrary postures, the wild pounding of rhythms and sound, will be multiplied, added to by a kind of mirroring of the gestures and postures, consisting of the accumulation of all the impulsive gestures, all the abortive postures, all the lapses in the mind and of the tongue by which speech's incapabilities are revealed, and on occasion we will not fail to turn to this stupendous existing wealth of expression.

Besides, there is a tangible idea of music where sound enters like a character, where harmonies are cut in two and become lost precisely as words break in.

Connections, level, are established between one means of expression and another; even lighting can have a predetermined intellectual meaning.

Musical Instruments: These will be used as objects, as part of the set. Moreover they need to act deeply and directly on our sensibility through the senses, and from the point of view of sound they invite research into utterly unusual sound properties and vibrations which present-day musical instruments do not possess, urging us to use ancient or forgotten instruments or to invent new ones. Apart from music, research is also needed into instruments and appliances based on special refining and new alloys which can reach a new scale in the octave and produce an unbearably piercing sound or noise.

Lights - Lighting: The lighting equipment currently in use in the theatre is no longer adequate. The particular action of light on the mind comes into play, we must discover oscillating light effects, new ways of diffusing lighting in waves, sheet lighting like a flight of fire-arrows. The colour scale of the equipment currently in use must be revised from start to finish. Fineness, density and opacity factors must be reintroduced into lighting, so as to produce special tonal properties, sensations of heat, cold, anger, fear and so on.

Costume: As to costume, without believing there can be any uniform stage costume that would be the same for all plays, modern dress will be avoided as much as possible not because of a fetishistic superstition for the past, but because it is perfectly obvious certain age-old costumes of ritual intent, although they were once fashionable, retain a revealing beauty and appearance because of their closeness to the traditions which gave rise to them.

The Stage - The Auditorium: We intend to do away with stage and auditorium, replacing them by a kind of single, undivided locale without any partitions of any kind and this will become the very scene of the action. Direct contact will be established between the audience and the show, between actors and audience, from the very fact that the audience is seated in the centre of the action, is encircled and furrowed by it. This encirclement comes from the shape of the house itself.

Abandoning the architecture of present-day theatres, we will rent some kind of barn or hangar rebuilt along lines culminating in the architecture of some churches, holy places, or certain Tibetan temples.

This building will have special interior height and depth dimensions. The auditorium will be enclosed within four walls stripped of any ornament, with the audience seated below, in the middle, on swivelling chairs allowing them to follow the show taking place around them. In effect, the lack of a stage in the normal sense of the word will permit the action to extend itself to the four corners of the auditorium. Special places will be set aside for the actors and action in the four cardinal points of the hall. Scenes will be acted in front of washed walls designed to absorb light. In addition, overhead galleries run right around the circumference of the room as in some Primitive paintings. These galleries will enable actors to pursue one another from one corner of the hall to the other as needed, and the action can extend in all directions at all perspective levels of height and depth. A shout could be transmitted by word of mouth from one end to the other with a succession of amplifications and inflections. The action will unfold, extending its trajectory from floor to floor, from place to place, with sudden outbursts flaring up in different spots like conflagrations. And the show's truly illusive nature will no longer be a hollow gesture any more than will the action's direct, immediate hold on the spectators. For the action, diffused over a vast area, will require the lighting for one scene and the varied lighting for a performance to hold the audience as well as the characters - and physical lighting methods, the thunder and wind whose repercussions will be experienced by the spectators, will correspond with several actions at once, several phases in one action with the characters clinging together like swarms, will endure all the onslaughts of the situations and the external assaults of weather and storms.

However, a central site will be retained which, without acting as a stage properly speaking, enables the body of the action to be concentrated and brought to a climax whenever necessary.

Objects-Masks-Props: Puppets, huge masks, objects of strange proportions appear by the same right as verbal imagery, stressing the physical aspect of all imagery and expression - with the corollary that all objects requiring a stereotyped physical representation will be discarded or disguised.

Decor: No decor. Hieroglyphic characters, ritual costume, thirty foot high effigies of King Lear's beard in the storm, musical instruments as tall as men, objects of unknown form and purpose are enough to fulfil this function.

Topicality: But, you may say, theatre so removed from life, facts or present-day activities... news and events, yes! Anxieties, whatever is profound about them, the prerogative of the few, no! In the Zohar, the story of Rabbi Simeon is as inflammatory as fire, as topical as fire.

Works: We will not act scripted plays but will attempt to stage productions straight from subjects, facts or known works. The type and lay-out of the auditorium itself governs the show as no theme, however vast, is forbidden to us.

Show: We must revive the concept of 'an integral show. The problem is to express it, spatially nourish and furnish it like tap-holes drilled into aflat wall of rock, suddenly generating geysers and bouquets of stone.

The Actor: The actor is both a prime factor, since the show's success depends on the effectiveness of his acting, as well as a kind of neutral, pliant factor since he is rigorously denied any individual initiative. Besides, this is a field where there are no exact rules. And there is a wide margin dividing a man from an instrument, between an actor required to give nothing more than a certain number of sobs and one who has to deliver a speech, using his own powers of persuasion.

Interpretation: The show will be coded from start to finish, like a language. Thus no moves will be wasted, all obeying a rhythm, every character being typified to the nth degree, each gesture, feature and costume to appear as so many shafts of light.

Cinema: Through poetry, theatre contrasts pictures of the unformu-lated with the crude visualization of what exists. Besides, from an action viewpoint, one cannot compare a cinema image, however poetic it may be, since it is restricted by the film, with a theatre image which obeys all life's requirements.

Cruelty: There can be no spectacle without an element of cruelty as the basis of every show. In our present degenerative state, metaphysics must be made to enter the mind through the body. . . .

The Balinese theater has revealed to us a physical and non¬verbal idea of the theater, in which the theater is contained within the limits of everything that can happen on a stage, independently of the written text, whereas the theater as we conceive it in the Occident has declared its alliance with the text and finds itself limited by it. For the Occidental theater the Word is everything, and there is no possibility of expression without it; the theater is a branch of literature, a kind of sonorous species of language, and even if we admit a differ¬ence between the text spoken on the stage and the text read by the eyes, if we restrict theater to what happens between cues, we have still not managed to separate it from the idea of a performed text.

This idea of the supremacy of speech in the theater is so deeply rooted in us, and the theater seems to such a degree merely the material reflection of the text, that everything in the theater that exceeds this text, that is not kept within its limits and strictly conditioned by it, seems to us purely a mat¬ter of mise en scene, and quite inferior in comparison with the text.

Presented with this subordination of theater to speech, one might indeed wonder whether the theater by any chance possesses its own language, whether it is entirely fanciful to consider it as an independent and autonomous art, of the same rank as music, painting, dance, etc. . . .

One finds in any case that this language, if it exists, is nec¬essarily identified with the mise en scene considered:

1. as the visual and plastic materialization of speech,

2. as the language of everything that can be said and signi¬fied upon a stage independently of speech, everything that finds its expression in space, or that can be affected or disintegrated by it.

Once we regard this language of the mise en scene as the pure theatrical language, we must discover whether it can attain the same internal ends as speech, whether theatrically and from the point of view of the mind it can claim the same intellectual efficacy as the spoken language. One can wonder, in other words, whether it has the power, not to define thoughts but to cause thinking, whether it may not entice the mind to take profound and efficacious attitudes toward it from its own point of view.

In a word, to raise the question of the intellectual efficacy of expression by means of objective forms, of the intellectual efficacy of a language which would use only shapes, or noise, or gesture, is to raise the question of the intellectual efficacy of art.

If we have come to attribute to art nothing more than the values of pleasure and relaxation and constrain it to a purely formal use of forms within the harmony of certain external -relations, that in no way spoils its profound expressive value; but the spiritual infirmity of the Occident, which is the place par excellence where men have confused art and aestheticism, is to think that its painting would function only as painting, dance which would be merely plastic, as if in an attempt to castrate the forms of art, to sever their ties with all the mystic attitudes they might acquire in confrontation with the absolute.

One therefore understands that the theater, to the very degree that it remains confined within its own language and in correlation with it, must break with actuality. Its object is not to resolve social or psychological conflicts, to serve as battlefield for moral passions, but to express objectively cer¬tain secret truths, to bring into the light of day by means of active gestures certain aspects of truth that have been buried under forms in their encounters with Becoming.

To do that, to link the theater to the expressive possibilities of forms, to everything in the domain of gestures, noises, colors, movements, etc., is to restore it to its original direction, to reinstate it in its religious and metaphysical aspect, is to reconcile it with the universe.

But words, it will be said, have metaphysical powers; it is not forbidden to conceive of speech as well as of gestures on the universal level, and it is on that level moreover that speech acquires its major efficacy, like a dissociative force exerted upon physical appearances, and upon all states in which the mind feels stabilized and tends towards repose. And we can readily answer that this metaphysical way of considering speech is not that of the Occidental theater, which employs speech not as an active force springing out of the destruction of appearances in order to reach the mind itself, but on the contrary as a completed stage of thought which is lost at the moment of its own exteriorization.

Speech in the Occidental theater is used only to express psychological conflicts particular to man and the daily reality of his life. His conflicts are clearly accessible to spoken lan¬guage, and whether they remain in the psychological sphere or leave it to enter the social sphere, the interest of the drama will still remain a moral one according to the way in which its conflicts attack and disintegrate the characters. And it will indeed always be a matter of a domain in which the verbal solutions of speech will retain their advantage. But these moral conflicts by their very nature have no absolute need of the stage to be resolved. To cause spoken language or expression by words to dominate on the stage the objective expression of gestures and of everything which affects the mind by sensuous and spatial means is to turn one's back on the physical neces¬sities of the stage and to rebel against its possibilities.

It must be said that the domain of the theater is not psycho¬logical but plastic and physical. And it is not a question of whether the physical language of theater is capable of achiev¬ing the same psychological resolutions as the language of words, whether it is able to express feelings and passions as well as words, but whether there are not attitudes in the realm of thought and intelligence that words are incapable of grasp¬ing and that gestures and everything partaking of a spatial language attain with more precision than they.

Before giving an example of the relations between the phy¬sical world and the deepest states of mind, let me quote what I have written elsewhere:

"All true feeling is in reality untranslatable. To express it is to betray it. But to translate it is to dissimulate it. True ex¬pression hides what it makes manifest. It sets the mind in opposition to the real void of nature by creating in reaction a kind of fullness in thought. Or, in other terms, in relation to the manifestation-illusion of nature it creates a void in thought. All powerful feeling produces in us the idea of the void. And the lucid language which obstructs the appearance of this void also obstructs the appearance of poetry in thought. That is why an image, an allegory, a figure that masks what it would reveal have more significance for the spirit than the lucidities of speech and its analytics.

"This is why true beauty never strikes us directly. The setting sun is beautiful because of all it makes us lose."

The nightmares of Flemish painting strike us by the juxta¬position with the real world of what is only a caricature of that world; they offer the specters we encounter in our dreams. They originate in those half-dreaming states that produce clumsy, ambiguous gestures and embarrassing slips of the tongue: beside a forgotten child they place a leaping harp; near a human embryo swimming in underground waterfalls they show an army's advance against a redoubtable fortress. Be¬side the imaginary uncertainty the march of certitude, and beyond a yellow subterranean light the orange flash of a great autumn sun just about to set.

It is not a matter of suppressing speech in the theater but of changing its role, and especially of reducing its position, of considering it as something else than a means of conducting human characters to their external ends, since the theater is concerned only with the way feelings and passions conflict with one another, and man with man, in life.

To change the role of speech in theater is to make use of it in a concrete and spatial sense, combining it with everything in the theater that is spatial and significant in the concrete domain;—to manipulate it like a solid object, one which overturns and disturbs things, in the air first of all, then in an infinitely more mysterious and secret domain but one that admits of extension, and it will not be very difficult to identify this secret but extended domain with that of formal anarchy on the one hand but also with that of continuous formal crea¬tion on the other.

This is why the identification of the theater's purpose with every possibility of formal and extended manifestation gives rise to the idea of a certain poetry in space which itself is taken for sorcery.

In the Oriental theater of metaphysical tendency, contrasted to the Occidental theater of psychological tendency, forms assume and extend their sense and their significations on all possible levels; or, if you will, they set up vibrations not on a single level, but on every level of the mind at once.

And it is because of the multiplicity of their aspects that they can disturb and charm and continuously excite the mind. It is because the Oriental theater does not deal with the external aspects of things on a single level nor rest content with the simple obstacle or with the impact of these aspects on the senses, but instead considers the degree of mental possibil¬ity from which they issue, that it participates in the intense poetry of nature and preserves its magic relations with all the objective degrees of universal magnetism.

It is in the light of magic and sorcery that the mise en scene must be considered, not as the reflection of a writtten text, the mere projection of physical doubles that is derived from the written work, but as the burning projection of all the objective consequences of a gesture, word, sound, music, and their com¬binations. This active projection can be made only upon the stage and its consequences found in the presence of and upon the stage; and the author who uses written words only has nothing to do with the theater and must give way to specialists in its objective and animated sorcery.

No More Masterpieces

One of the reasons for the asphyxiating atmosphere in which we live without possible escape or remedy—and in which we all share, even the most revolutionary among us—is our re¬spect for what has been written, formulated, or painted, what has been given form, as if all expression were not at last ex¬hausted, were not at a point where things must break apart if they are to start anew and begin fresh.

We must have done with this idea of masterpieces reserved for a self-styled elite and not understood by the general public; the mind has no such restricted districts as those so often used for clandestine sexual encounters.

Masterpieces of the past are good for the past: they are not good for us. We have the right to say what has been said and even what has not been said in a way that belongs to us, a way that is immediate and direct, corresponding to present modes of feeling, and understandable to everyone.

It is idiotic to reproach the masses for having no sense of the sublime, when the sublime is confused with one or another of its formal manifestations, which are moreover always de¬funct manifestations. And if for example a contemporary pub¬lic does not understand Oedipus Rex, I shall make bold to say that it is the fault of Oedipus Rex and not of the public.

In Oedipus Rex there is the theme of incest and the idea that nature mocks at morality and that there are certain unspecified powers at large which we would do well to beware of, call them destiny or anything you choose.

There is in addition the presence of a plague epidemic which is a physical incarnation of these powers. But the whole in a manner and language that have lost all touch with the rude and epileptic rhythm of our time. Sophocles speaks grandly perhaps, but in a style that is no longer timely. His language is too refined for this age, it is as if he were speaking beside the point.

However, a public that shudders at train wrecks, that is familiar with earthquakes, plagues, revolutions, wars; that is sensitive to the disordered anguish of love, can be affected by all these grand notions and asks only to become aware of them, but on condition that it is addressed in its own language, and that its knowledge of these things does not come to it through adulterated trappings and speech that belong to extinct eras which will never live again.

Today as yesterday, the public is greedy for mystery: it asks only to become aware of the laws according to which destiny manifests itself, and to divine perhaps the secret of its appari¬tions.

Let us leave textual criticism to graduate students, formal criticism to esthetes, and recognize that what has been said is not still to be said; that an expression does not have the same value twice, does not live two lives; that all words, once spoken, are dead and function only at the moment when they are uttered, that a form, once it has served, cannot be used again and asks only to be replaced by another, and that the theater is the only place in the world where a gesture, once made, can never be made the same way twice.

If the public does not frequent our literary masterpieces, it is because those masterpieces are literary, that is to say, fixed; and fixed in forms that no longer respond to the needs of the time.

Far from blaming the public, we ought to blame the formal screen we interpose between ourselves and the public, and this new form of idolatry, the idolatry of fixed masterpieces which is one of the aspects of bourgeois conformism.

This conformism makes us confuse sublimity, ideas, and things with the forms they have taken in time and in our minds—in our snobbish, precious, aesthetic mentalities which the public does not understand.

How pointless in such matters to accuse the public of bad taste because it relishes insanities, so long as the public is not shown a valid spectacle; and I defy anyone to show me here a spectacle valid—valid in the supreme sense of the theater— since the last great romantic melodramas, i.e., since a hundred years ago.

The public, which takes the false for the true, has the sense of the true and always responds to it when it is manifested. However it is not upon the stage that the true is to be sought nowadays, but in the street; and if the crowd in the street is offered an occasion to show its human dignity, it will always do so.

If people are out of the habit of going to the theater, if we have all finally come to think of theater as an inferior art, a means of popular distraction, and to use it as an outlet for our worst instincts, it is because we have learned too well what the theater has been, namely, falsehood and illusion. It is be¬cause we have been accustomed for four hundred years, that is since the Renaissance, to a purely descriptive and narrative theater—story telling psychology; it is because every possible ingenuity has been exerted in bringing to life on the stage plausible but detached beings, with the spectacle on one side, the public on the other—and because the public is no longer shown anything but the mirror of itself.

Shakespeare himself is responsible for this aberration and decline, this disinterested idea of the theater which wishes a theatrical performance to leave the public intact, without setting off one image that will shake the organism to its foundations and leave an ineffaceable scar.

If, in Shakespeare, a man is sometimes preoccupied with what transcends him, it is always in order to determine the ultimate consequences of this preoccupation within him, i.e., psychology.

Psychology, which works relentlessly to reduce the un¬known to the known, to the quotidian and the ordinary, is the cause of the theater's abasement and its fearful loss of energy, which seems to me to have reached its lowest point. And I think both the theater and we ourselves have had enough of psychology.

I believe furthermore that we can all agree on this matter sufficiently so that there is no need to descend to the repug¬nant level of the modern and French theater to condemn the theater of psychology.

Stories about money, worry over money, social careerism, the pangs of love unspoiled by altruism, sexuality sugar-coated with an eroticism that has lost its mystery have nothing to do with the theater, even if they do belong to psychology. These torments, seductions, and lusts before which we are nothing but Peeping Toms gratifying our cravings, tend to go bad, and their rot turns to revolution: we must take this into account.

But this is not our most serious concern.

If Shakespeare and his imitators have gradually insinuated the idea of art for art's sake, with art on one side and life on the other, we can rest on this feeble and lazy idea only as long as the life outside endures. But there are too many signs that everything that used to sustain our lives no longer does so, that we are all mad, desperate, and sick. And I call for us to react.

This idea of a detached art, of poetry as a charm which exists only to distract our leisure, is a decadent idea and an unmistakable symptom of our power to castrate. . . .

The Theatre of Cruelty - First Manifesto

We cannot continue to prostitute the idea of theatre whose only value lies in its agonizing, magic relationship to reality and danger.

Put in this way, the problem of theatre must arouse universal attention, it being understood that theatre, through its physical aspect and because it requires spatial expression (the only real one in fact) allows the sum total of the magic means in the arts and words to be organically active like renewed exorcisms. From the aforementioned it becomes apparent that theatre will never recover its own specific powers of action until it has also recovered its own language.

That is, instead of harking back to texts regarded as sacred and definitive, we must first break theatre's subjection to the text and rediscover the idea of a kind of unique language somewhere between gesture and thought. [. . .]

TECHNIQUE

The problem is to turn theatre into a function in the proper sense of the word, something as exactly localized as the circulation of our blood through our veins, or the apparently chaotic evolution of dream images in the mind, by an effective mix, truly enslaving our attention.

Theatre will never be itself again, that is to say will never be able to form truly illusive means, unless it provides the audience with truthful distillations of dreams where its taste for crime, its erotic obsessions, its savageness, its fantasies, its Utopian sense of life and objects, even its cannibalism, do not gush out on an illusory make-believe, but on an inner level.

In other words, theatre ought to pursue a re-examination not only of all aspects of an objective, descriptive outside world but also all aspects of an inner world, that is to say man viewed meta¬physically, by every means at its disposal. We believe that only in this way will we be able to talk about imagination's rights in the theatre once more. Neither Humur, Poetry nor Imagination mean anything unless they re-examine man organically through anarchic destruction, his ideas on reality and his poetic vision in reality, generating stupendous flights of form constituting the whole show.

But to view theatre as a second-hand psychological or moral operation and to believe dreams themselves only serve as a substitute is to restrict both dreams' and theatre's deep poetic range. If theatre is as bloody and as inhuman as dreams, the reason for this is that it perpetuates the metaphysical notions in some Fables in a present-day, tangible manner, whose atrocity and energy are enough to prove their origins and intentions in funda¬mental first principles rather than to reveal and unforgettably tie down the idea of continual conflict within us, where life is continually lacerated, where everything in creation rises up and attacks our condition as created beings.

This being so, we can see that by its proximity to the first principles poetically infusing it with energy, this naked theatre language, a non-virtual but real language using man's nervous magnetism, must allow us to transgress the ordinary limits of art and words, actively, that is to say, magically, to produce a kind of total creation in real terms, where man must reassume his position between dreams and events.

SUBJECTS

We do not mean to bore the audience to death with transcendental cosmic preoccupations. Audiences are not interested whether there are profound clues to the show's thought and action, since in general this does not concern them. But these must still be there and that concerns us.

The Show: Every show will contain physical, objective elements per¬ceptible to all. Shouts, groans, apparitions, surprise, dramatic moments of all kinds, the magic beauty of the costumes modelled on certain ritualistic patterns, brilliant lighting, vocal, incantational beauty, attractive harmonies, rare musical notes, colours of objects, the physical rhythm of the moves whose build and fall will be wedded to the beat of moves familiar to all, the tangible appearance of new, surprising objects, masks, puppets many feet high, abrupt lighting changes, the physical action of lighting stimulating heat and cold, and so on.

Staging: This archetypal theatre language will be formed around staging not simply viewed as one degree of refraction of the script on stage, but as the starting point for theatrical creation. And the old duality between author and director will disappear, to be replaced by a kind of single Creator using and handling this language, responsible both for the play and the action.

Stage Language: We do not intend to do away with dialogue, but to give words something of the significance they have in dreams.

Moreover we must find new ways of recording this language, whether these ways are similar to musical notation or to some kind of code.

As to ordinary objects, or even the human body, raised to the dignity of signs, we can obviously take our inspiration from hieroglyphic characters not only to transcribe these signs legibly so they can be reproduced at will, but to compose exact symbols on stage that are immediately legible.

Then again, this coding and musical notation will be valuable as a means of vocal transcription.

Since the basis of this language is to initiate a special use of inflections, these must take up a kind of balanced harmony, a subsidiary exaggeration of speech able to be reproduced at will.

Similarly the thousand and one facial expressions caught in the form of masks can be listed and labeled so they may directly and symbolically participate in this tangible stage language, independently of their particular psychological use.

Furthermore, these symbolic gestures, masks, postures, individual or group moves, whose countless meanings constitute an important part of the tangible stage language of evocative gestures, emotive arbitrary postures, the wild pounding of rhythms and sound, will be multiplied, added to by a kind of mirroring of the gestures and postures, consisting of the accumulation of all the impulsive gestures, all the abortive postures, all the lapses in the mind and of the tongue by which speech's incapabilities are revealed, and on occasion we will not fail to turn to this stupendous existing wealth of expression.

Besides, there is a tangible idea of music where sound enters like a character, where harmonies are cut in two and become lost precisely as words break in.

Connections, level, are established between one means of expression and another; even lighting can have a predetermined intellectual meaning.

Musical Instruments: These will be used as objects, as part of the set. Moreover they need to act deeply and directly on our sensibility through the senses, and from the point of view of sound they invite research into utterly unusual sound properties and vibrations which present-day musical instruments do not possess, urging us to use ancient or forgotten instruments or to invent new ones. Apart from music, research is also needed into instruments and appliances based on special refining and new alloys which can reach a new scale in the octave and produce an unbearably piercing sound or noise.

Lights - Lighting: The lighting equipment currently in use in the theatre is no longer adequate. The particular action of light on the mind comes into play, we must discover oscillating light effects, new ways of diffusing lighting in waves, sheet lighting like a flight of fire-arrows. The colour scale of the equipment currently in use must be revised from start to finish. Fineness, density and opacity factors must be reintroduced into lighting, so as to produce special tonal properties, sensations of heat, cold, anger, fear and so on.

Costume: As to costume, without believing there can be any uniform stage costume that would be the same for all plays, modern dress will be avoided as much as possible not because of a fetishistic superstition for the past, but because it is perfectly obvious certain age-old costumes of ritual intent, although they were once fashionable, retain a revealing beauty and appearance because of their closeness to the traditions which gave rise to them.

The Stage - The Auditorium: We intend to do away with stage and auditorium, replacing them by a kind of single, undivided locale without any partitions of any kind and this will become the very scene of the action. Direct contact will be established between the audience and the show, between actors and audience, from the very fact that the audience is seated in the centre of the action, is encircled and furrowed by it. This encirclement comes from the shape of the house itself.

Abandoning the architecture of present-day theatres, we will rent some kind of barn or hangar rebuilt along lines culminating in the architecture of some churches, holy places, or certain Tibetan temples.

This building will have special interior height and depth dimensions. The auditorium will be enclosed within four walls stripped of any ornament, with the audience seated below, in the middle, on swivelling chairs allowing them to follow the show taking place around them. In effect, the lack of a stage in the normal sense of the word will permit the action to extend itself to the four corners of the auditorium. Special places will be set aside for the actors and action in the four cardinal points of the hall. Scenes will be acted in front of washed walls designed to absorb light. In addition, overhead galleries run right around the circumference of the room as in some Primitive paintings. These galleries will enable actors to pursue one another from one corner of the hall to the other as needed, and the action can extend in all directions at all perspective levels of height and depth. A shout could be transmitted by word of mouth from one end to the other with a succession of amplifications and inflections. The action will unfold, extending its trajectory from floor to floor, from place to place, with sudden outbursts flaring up in different spots like conflagrations. And the show's truly illusive nature will no longer be a hollow gesture any more than will the action's direct, immediate hold on the spectators. For the action, diffused over a vast area, will require the lighting for one scene and the varied lighting for a performance to hold the audience as well as the characters - and physical lighting methods, the thunder and wind whose repercussions will be experienced by the spectators, will correspond with several actions at once, several phases in one action with the characters clinging together like swarms, will endure all the onslaughts of the situations and the external assaults of weather and storms.

However, a central site will be retained which, without acting as a stage properly speaking, enables the body of the action to be concentrated and brought to a climax whenever necessary.

Objects-Masks-Props: Puppets, huge masks, objects of strange proportions appear by the same right as verbal imagery, stressing the physical aspect of all imagery and expression - with the corollary that all objects requiring a stereotyped physical representation will be discarded or disguised.

Decor: No decor. Hieroglyphic characters, ritual costume, thirty foot high effigies of King Lear's beard in the storm, musical instruments as tall as men, objects of unknown form and purpose are enough to fulfil this function.

Topicality: But, you may say, theatre so removed from life, facts or present-day activities... news and events, yes! Anxieties, whatever is profound about them, the prerogative of the few, no! In the Zohar, the story of Rabbi Simeon is as inflammatory as fire, as topical as fire.

Works: We will not act scripted plays but will attempt to stage productions straight from subjects, facts or known works. The type and lay-out of the auditorium itself governs the show as no theme, however vast, is forbidden to us.

Show: We must revive the concept of 'an integral show. The problem is to express it, spatially nourish and furnish it like tap-holes drilled into aflat wall of rock, suddenly generating geysers and bouquets of stone.

The Actor: The actor is both a prime factor, since the show's success depends on the effectiveness of his acting, as well as a kind of neutral, pliant factor since he is rigorously denied any individual initiative. Besides, this is a field where there are no exact rules. And there is a wide margin dividing a man from an instrument, between an actor required to give nothing more than a certain number of sobs and one who has to deliver a speech, using his own powers of persuasion.

Interpretation: The show will be coded from start to finish, like a language. Thus no moves will be wasted, all obeying a rhythm, every character being typified to the nth degree, each gesture, feature and costume to appear as so many shafts of light.

Cinema: Through poetry, theatre contrasts pictures of the unformu-lated with the crude visualization of what exists. Besides, from an action viewpoint, one cannot compare a cinema image, however poetic it may be, since it is restricted by the film, with a theatre image which obeys all life's requirements.

Cruelty: There can be no spectacle without an element of cruelty as the basis of every show. In our present degenerative state, metaphysics must be made to enter the mind through the body. . . .

1 comment:

Thank you

Post a Comment