Tuesday, December 9, 2008

Monday, December 8, 2008

Sunday, November 23, 2008

'PSYCHOHamlet,’ qu’est-ce que c’est?

BY BRETT BROWN

From The Yale Herald, April 16 2006

Fri., Apr. 14: At 8 p.m., 30 Yale students board a bus at Phelps Gate. They are shipped off to an undisclosed off-campus location where they will view, and actively participate in, PSYCHOHamlet, which, as the title indicates, incorporates elements of both Hitch-cock’s Psycho and Shakespeare’s Hamlet.The one-man play—the first collaboration between undergraduates, Yale faculty, and the Yale School of Art—is the senior project of Satya Bhabha, BK ’06, who wrote and performs in it.

Last summer, Bhabha, a Theatre Studies major, started work on his senior project. He knew that he “wanted to do something classical, and also with a small cast” and so happened upon the idea of a one-man Hamlet. As he studied the play, he realized that the ghost of Hamlet may have been created by its protagonist: “As I worked through the script and looked at Act I, my interpretation made clear to me the possibility that Hamlet conjured the ghost,” Bhabha said. He was reminded of another famously tormented character: Psycho’s Norman Bates. As he continued to study Shakespeare’s text, more and more similarities emerged. From superficial parallels in plot—the death of a father, a son obsessed with his mother, murder behind curtains—to the governing effect of the works, Bhabha found that Psycho and Hamlet inhabited the same emotional world and explored similar themes. It seemed natural, then, for Bhabha to combine the two “icons of culture”; in doing so, he enlisted Theater Studies professor Joseph Roach, who directed the show, and Derek Larson, ART ’07, who has made a video installation for it.

But the show is not merely a hodgepodge of play and film; nor is it just a medley of Hamlet and Psycho’s most exciting bits. Rather, it is a new work, which uses the different perspectives of Hitchcock and Shakespeare—and the different media of film and live theater—to explore one world of feeling. “I looked at the script of Hamletand the screenplay of Psychoas two text sources,” Bhabha said. “I sculpted the show not about Hamletor about Psychobut about the sort of tenuous connection between emotion and insanity.” When asked how he achieved this, Bhabha responded, “I’ll not speak to that. [People] will have to come see the show.”

Seeing the show, however, takes some effort. Rather than shuffling over to the Off-Broadway Theater, audience members—no more than 30—meet each night at Phelps Gate at 7:30 p.m. At 7:45, unclaimed reservations are released, and at 8, the bus leaves for an unknown, eerie locale. To be concrete, the would-be theater is not affiliated with Yale. Producer Andrew Law, DC ’08, said cryptically that the space is owned by an “outside corporation” to whom the production paid a rental fee. It is, he said, “a raw space—no piping to hang lights, no sound system.” To be vague and grand—as Professor Roach was—you could call this area “the womb of mechanized death.” However they referred to it, though, all the people involved in the production are thrilled to work in this space.

Roach, a professor in both the Theatre Studies and the English departments, believed that the venue adds a new layer to the theatrical experience. He volunteered to direct Bhabha’s senior project because he believes Bhabha is “exceptionally talented and has great ideas.” And, although Roach thought that Bhabha’s writing and performance would be effective anywhere, he believed that the current location “gives us a chance to step outside the usual expected venues. It is a very evocative space.” For Bhabha, it was important that the audience be placed in an unfamiliar environment, that they be “really challenged.” The show grew out of its location: Bhabha has been working there for over a month.

PSYCHOHamlet is a rare project in combining the diverging perspectives of its various authors with the ideas of its crew. With various media and an unusual venue, Bhabha and his team intend to evoke depression, melancholy, and insanity. It is a production shrouded in secrecy, but one with the potential to come across as inspired, and a little bit psycho.

Tuesday, November 18, 2008

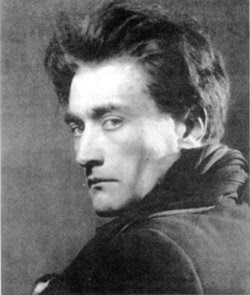

ANTONIN ARTAUD (1894-1948)

The Balinese theater has revealed to us a physical and non¬verbal idea of the theater, in which the theater is contained within the limits of everything that can happen on a stage, independently of the written text, whereas the theater as we conceive it in the Occident has declared its alliance with the text and finds itself limited by it. For the Occidental theater the Word is everything, and there is no possibility of expression without it; the theater is a branch of literature, a kind of sonorous species of language, and even if we admit a differ¬ence between the text spoken on the stage and the text read by the eyes, if we restrict theater to what happens between cues, we have still not managed to separate it from the idea of a performed text.

This idea of the supremacy of speech in the theater is so deeply rooted in us, and the theater seems to such a degree merely the material reflection of the text, that everything in the theater that exceeds this text, that is not kept within its limits and strictly conditioned by it, seems to us purely a mat¬ter of mise en scene, and quite inferior in comparison with the text.

Presented with this subordination of theater to speech, one might indeed wonder whether the theater by any chance possesses its own language, whether it is entirely fanciful to consider it as an independent and autonomous art, of the same rank as music, painting, dance, etc. . . .

One finds in any case that this language, if it exists, is nec¬essarily identified with the mise en scene considered:

1. as the visual and plastic materialization of speech,

2. as the language of everything that can be said and signi¬fied upon a stage independently of speech, everything that finds its expression in space, or that can be affected or disintegrated by it.

Once we regard this language of the mise en scene as the pure theatrical language, we must discover whether it can attain the same internal ends as speech, whether theatrically and from the point of view of the mind it can claim the same intellectual efficacy as the spoken language. One can wonder, in other words, whether it has the power, not to define thoughts but to cause thinking, whether it may not entice the mind to take profound and efficacious attitudes toward it from its own point of view.

In a word, to raise the question of the intellectual efficacy of expression by means of objective forms, of the intellectual efficacy of a language which would use only shapes, or noise, or gesture, is to raise the question of the intellectual efficacy of art.

If we have come to attribute to art nothing more than the values of pleasure and relaxation and constrain it to a purely formal use of forms within the harmony of certain external -relations, that in no way spoils its profound expressive value; but the spiritual infirmity of the Occident, which is the place par excellence where men have confused art and aestheticism, is to think that its painting would function only as painting, dance which would be merely plastic, as if in an attempt to castrate the forms of art, to sever their ties with all the mystic attitudes they might acquire in confrontation with the absolute.

One therefore understands that the theater, to the very degree that it remains confined within its own language and in correlation with it, must break with actuality. Its object is not to resolve social or psychological conflicts, to serve as battlefield for moral passions, but to express objectively cer¬tain secret truths, to bring into the light of day by means of active gestures certain aspects of truth that have been buried under forms in their encounters with Becoming.

To do that, to link the theater to the expressive possibilities of forms, to everything in the domain of gestures, noises, colors, movements, etc., is to restore it to its original direction, to reinstate it in its religious and metaphysical aspect, is to reconcile it with the universe.

But words, it will be said, have metaphysical powers; it is not forbidden to conceive of speech as well as of gestures on the universal level, and it is on that level moreover that speech acquires its major efficacy, like a dissociative force exerted upon physical appearances, and upon all states in which the mind feels stabilized and tends towards repose. And we can readily answer that this metaphysical way of considering speech is not that of the Occidental theater, which employs speech not as an active force springing out of the destruction of appearances in order to reach the mind itself, but on the contrary as a completed stage of thought which is lost at the moment of its own exteriorization.

Speech in the Occidental theater is used only to express psychological conflicts particular to man and the daily reality of his life. His conflicts are clearly accessible to spoken lan¬guage, and whether they remain in the psychological sphere or leave it to enter the social sphere, the interest of the drama will still remain a moral one according to the way in which its conflicts attack and disintegrate the characters. And it will indeed always be a matter of a domain in which the verbal solutions of speech will retain their advantage. But these moral conflicts by their very nature have no absolute need of the stage to be resolved. To cause spoken language or expression by words to dominate on the stage the objective expression of gestures and of everything which affects the mind by sensuous and spatial means is to turn one's back on the physical neces¬sities of the stage and to rebel against its possibilities.

It must be said that the domain of the theater is not psycho¬logical but plastic and physical. And it is not a question of whether the physical language of theater is capable of achiev¬ing the same psychological resolutions as the language of words, whether it is able to express feelings and passions as well as words, but whether there are not attitudes in the realm of thought and intelligence that words are incapable of grasp¬ing and that gestures and everything partaking of a spatial language attain with more precision than they.

Before giving an example of the relations between the phy¬sical world and the deepest states of mind, let me quote what I have written elsewhere:

"All true feeling is in reality untranslatable. To express it is to betray it. But to translate it is to dissimulate it. True ex¬pression hides what it makes manifest. It sets the mind in opposition to the real void of nature by creating in reaction a kind of fullness in thought. Or, in other terms, in relation to the manifestation-illusion of nature it creates a void in thought. All powerful feeling produces in us the idea of the void. And the lucid language which obstructs the appearance of this void also obstructs the appearance of poetry in thought. That is why an image, an allegory, a figure that masks what it would reveal have more significance for the spirit than the lucidities of speech and its analytics.

"This is why true beauty never strikes us directly. The setting sun is beautiful because of all it makes us lose."

The nightmares of Flemish painting strike us by the juxta¬position with the real world of what is only a caricature of that world; they offer the specters we encounter in our dreams. They originate in those half-dreaming states that produce clumsy, ambiguous gestures and embarrassing slips of the tongue: beside a forgotten child they place a leaping harp; near a human embryo swimming in underground waterfalls they show an army's advance against a redoubtable fortress. Be¬side the imaginary uncertainty the march of certitude, and beyond a yellow subterranean light the orange flash of a great autumn sun just about to set.

It is not a matter of suppressing speech in the theater but of changing its role, and especially of reducing its position, of considering it as something else than a means of conducting human characters to their external ends, since the theater is concerned only with the way feelings and passions conflict with one another, and man with man, in life.

To change the role of speech in theater is to make use of it in a concrete and spatial sense, combining it with everything in the theater that is spatial and significant in the concrete domain;—to manipulate it like a solid object, one which overturns and disturbs things, in the air first of all, then in an infinitely more mysterious and secret domain but one that admits of extension, and it will not be very difficult to identify this secret but extended domain with that of formal anarchy on the one hand but also with that of continuous formal crea¬tion on the other.

This is why the identification of the theater's purpose with every possibility of formal and extended manifestation gives rise to the idea of a certain poetry in space which itself is taken for sorcery.

In the Oriental theater of metaphysical tendency, contrasted to the Occidental theater of psychological tendency, forms assume and extend their sense and their significations on all possible levels; or, if you will, they set up vibrations not on a single level, but on every level of the mind at once.

And it is because of the multiplicity of their aspects that they can disturb and charm and continuously excite the mind. It is because the Oriental theater does not deal with the external aspects of things on a single level nor rest content with the simple obstacle or with the impact of these aspects on the senses, but instead considers the degree of mental possibil¬ity from which they issue, that it participates in the intense poetry of nature and preserves its magic relations with all the objective degrees of universal magnetism.

It is in the light of magic and sorcery that the mise en scene must be considered, not as the reflection of a writtten text, the mere projection of physical doubles that is derived from the written work, but as the burning projection of all the objective consequences of a gesture, word, sound, music, and their com¬binations. This active projection can be made only upon the stage and its consequences found in the presence of and upon the stage; and the author who uses written words only has nothing to do with the theater and must give way to specialists in its objective and animated sorcery.

No More Masterpieces

One of the reasons for the asphyxiating atmosphere in which we live without possible escape or remedy—and in which we all share, even the most revolutionary among us—is our re¬spect for what has been written, formulated, or painted, what has been given form, as if all expression were not at last ex¬hausted, were not at a point where things must break apart if they are to start anew and begin fresh.

We must have done with this idea of masterpieces reserved for a self-styled elite and not understood by the general public; the mind has no such restricted districts as those so often used for clandestine sexual encounters.

Masterpieces of the past are good for the past: they are not good for us. We have the right to say what has been said and even what has not been said in a way that belongs to us, a way that is immediate and direct, corresponding to present modes of feeling, and understandable to everyone.

It is idiotic to reproach the masses for having no sense of the sublime, when the sublime is confused with one or another of its formal manifestations, which are moreover always de¬funct manifestations. And if for example a contemporary pub¬lic does not understand Oedipus Rex, I shall make bold to say that it is the fault of Oedipus Rex and not of the public.

In Oedipus Rex there is the theme of incest and the idea that nature mocks at morality and that there are certain unspecified powers at large which we would do well to beware of, call them destiny or anything you choose.

There is in addition the presence of a plague epidemic which is a physical incarnation of these powers. But the whole in a manner and language that have lost all touch with the rude and epileptic rhythm of our time. Sophocles speaks grandly perhaps, but in a style that is no longer timely. His language is too refined for this age, it is as if he were speaking beside the point.

However, a public that shudders at train wrecks, that is familiar with earthquakes, plagues, revolutions, wars; that is sensitive to the disordered anguish of love, can be affected by all these grand notions and asks only to become aware of them, but on condition that it is addressed in its own language, and that its knowledge of these things does not come to it through adulterated trappings and speech that belong to extinct eras which will never live again.

Today as yesterday, the public is greedy for mystery: it asks only to become aware of the laws according to which destiny manifests itself, and to divine perhaps the secret of its appari¬tions.

Let us leave textual criticism to graduate students, formal criticism to esthetes, and recognize that what has been said is not still to be said; that an expression does not have the same value twice, does not live two lives; that all words, once spoken, are dead and function only at the moment when they are uttered, that a form, once it has served, cannot be used again and asks only to be replaced by another, and that the theater is the only place in the world where a gesture, once made, can never be made the same way twice.

If the public does not frequent our literary masterpieces, it is because those masterpieces are literary, that is to say, fixed; and fixed in forms that no longer respond to the needs of the time.

Far from blaming the public, we ought to blame the formal screen we interpose between ourselves and the public, and this new form of idolatry, the idolatry of fixed masterpieces which is one of the aspects of bourgeois conformism.

This conformism makes us confuse sublimity, ideas, and things with the forms they have taken in time and in our minds—in our snobbish, precious, aesthetic mentalities which the public does not understand.

How pointless in such matters to accuse the public of bad taste because it relishes insanities, so long as the public is not shown a valid spectacle; and I defy anyone to show me here a spectacle valid—valid in the supreme sense of the theater— since the last great romantic melodramas, i.e., since a hundred years ago.

The public, which takes the false for the true, has the sense of the true and always responds to it when it is manifested. However it is not upon the stage that the true is to be sought nowadays, but in the street; and if the crowd in the street is offered an occasion to show its human dignity, it will always do so.

If people are out of the habit of going to the theater, if we have all finally come to think of theater as an inferior art, a means of popular distraction, and to use it as an outlet for our worst instincts, it is because we have learned too well what the theater has been, namely, falsehood and illusion. It is be¬cause we have been accustomed for four hundred years, that is since the Renaissance, to a purely descriptive and narrative theater—story telling psychology; it is because every possible ingenuity has been exerted in bringing to life on the stage plausible but detached beings, with the spectacle on one side, the public on the other—and because the public is no longer shown anything but the mirror of itself.

Shakespeare himself is responsible for this aberration and decline, this disinterested idea of the theater which wishes a theatrical performance to leave the public intact, without setting off one image that will shake the organism to its foundations and leave an ineffaceable scar.

If, in Shakespeare, a man is sometimes preoccupied with what transcends him, it is always in order to determine the ultimate consequences of this preoccupation within him, i.e., psychology.

Psychology, which works relentlessly to reduce the un¬known to the known, to the quotidian and the ordinary, is the cause of the theater's abasement and its fearful loss of energy, which seems to me to have reached its lowest point. And I think both the theater and we ourselves have had enough of psychology.

I believe furthermore that we can all agree on this matter sufficiently so that there is no need to descend to the repug¬nant level of the modern and French theater to condemn the theater of psychology.

Stories about money, worry over money, social careerism, the pangs of love unspoiled by altruism, sexuality sugar-coated with an eroticism that has lost its mystery have nothing to do with the theater, even if they do belong to psychology. These torments, seductions, and lusts before which we are nothing but Peeping Toms gratifying our cravings, tend to go bad, and their rot turns to revolution: we must take this into account.

But this is not our most serious concern.

If Shakespeare and his imitators have gradually insinuated the idea of art for art's sake, with art on one side and life on the other, we can rest on this feeble and lazy idea only as long as the life outside endures. But there are too many signs that everything that used to sustain our lives no longer does so, that we are all mad, desperate, and sick. And I call for us to react.

This idea of a detached art, of poetry as a charm which exists only to distract our leisure, is a decadent idea and an unmistakable symptom of our power to castrate. . . .

The Theatre of Cruelty - First Manifesto

We cannot continue to prostitute the idea of theatre whose only value lies in its agonizing, magic relationship to reality and danger.

Put in this way, the problem of theatre must arouse universal attention, it being understood that theatre, through its physical aspect and because it requires spatial expression (the only real one in fact) allows the sum total of the magic means in the arts and words to be organically active like renewed exorcisms. From the aforementioned it becomes apparent that theatre will never recover its own specific powers of action until it has also recovered its own language.

That is, instead of harking back to texts regarded as sacred and definitive, we must first break theatre's subjection to the text and rediscover the idea of a kind of unique language somewhere between gesture and thought. [. . .]

TECHNIQUE

The problem is to turn theatre into a function in the proper sense of the word, something as exactly localized as the circulation of our blood through our veins, or the apparently chaotic evolution of dream images in the mind, by an effective mix, truly enslaving our attention.

Theatre will never be itself again, that is to say will never be able to form truly illusive means, unless it provides the audience with truthful distillations of dreams where its taste for crime, its erotic obsessions, its savageness, its fantasies, its Utopian sense of life and objects, even its cannibalism, do not gush out on an illusory make-believe, but on an inner level.

In other words, theatre ought to pursue a re-examination not only of all aspects of an objective, descriptive outside world but also all aspects of an inner world, that is to say man viewed meta¬physically, by every means at its disposal. We believe that only in this way will we be able to talk about imagination's rights in the theatre once more. Neither Humur, Poetry nor Imagination mean anything unless they re-examine man organically through anarchic destruction, his ideas on reality and his poetic vision in reality, generating stupendous flights of form constituting the whole show.

But to view theatre as a second-hand psychological or moral operation and to believe dreams themselves only serve as a substitute is to restrict both dreams' and theatre's deep poetic range. If theatre is as bloody and as inhuman as dreams, the reason for this is that it perpetuates the metaphysical notions in some Fables in a present-day, tangible manner, whose atrocity and energy are enough to prove their origins and intentions in funda¬mental first principles rather than to reveal and unforgettably tie down the idea of continual conflict within us, where life is continually lacerated, where everything in creation rises up and attacks our condition as created beings.

This being so, we can see that by its proximity to the first principles poetically infusing it with energy, this naked theatre language, a non-virtual but real language using man's nervous magnetism, must allow us to transgress the ordinary limits of art and words, actively, that is to say, magically, to produce a kind of total creation in real terms, where man must reassume his position between dreams and events.

SUBJECTS

We do not mean to bore the audience to death with transcendental cosmic preoccupations. Audiences are not interested whether there are profound clues to the show's thought and action, since in general this does not concern them. But these must still be there and that concerns us.

The Show: Every show will contain physical, objective elements per¬ceptible to all. Shouts, groans, apparitions, surprise, dramatic moments of all kinds, the magic beauty of the costumes modelled on certain ritualistic patterns, brilliant lighting, vocal, incantational beauty, attractive harmonies, rare musical notes, colours of objects, the physical rhythm of the moves whose build and fall will be wedded to the beat of moves familiar to all, the tangible appearance of new, surprising objects, masks, puppets many feet high, abrupt lighting changes, the physical action of lighting stimulating heat and cold, and so on.

Staging: This archetypal theatre language will be formed around staging not simply viewed as one degree of refraction of the script on stage, but as the starting point for theatrical creation. And the old duality between author and director will disappear, to be replaced by a kind of single Creator using and handling this language, responsible both for the play and the action.

Stage Language: We do not intend to do away with dialogue, but to give words something of the significance they have in dreams.

Moreover we must find new ways of recording this language, whether these ways are similar to musical notation or to some kind of code.

As to ordinary objects, or even the human body, raised to the dignity of signs, we can obviously take our inspiration from hieroglyphic characters not only to transcribe these signs legibly so they can be reproduced at will, but to compose exact symbols on stage that are immediately legible.

Then again, this coding and musical notation will be valuable as a means of vocal transcription.

Since the basis of this language is to initiate a special use of inflections, these must take up a kind of balanced harmony, a subsidiary exaggeration of speech able to be reproduced at will.

Similarly the thousand and one facial expressions caught in the form of masks can be listed and labeled so they may directly and symbolically participate in this tangible stage language, independently of their particular psychological use.

Furthermore, these symbolic gestures, masks, postures, individual or group moves, whose countless meanings constitute an important part of the tangible stage language of evocative gestures, emotive arbitrary postures, the wild pounding of rhythms and sound, will be multiplied, added to by a kind of mirroring of the gestures and postures, consisting of the accumulation of all the impulsive gestures, all the abortive postures, all the lapses in the mind and of the tongue by which speech's incapabilities are revealed, and on occasion we will not fail to turn to this stupendous existing wealth of expression.

Besides, there is a tangible idea of music where sound enters like a character, where harmonies are cut in two and become lost precisely as words break in.

Connections, level, are established between one means of expression and another; even lighting can have a predetermined intellectual meaning.

Musical Instruments: These will be used as objects, as part of the set. Moreover they need to act deeply and directly on our sensibility through the senses, and from the point of view of sound they invite research into utterly unusual sound properties and vibrations which present-day musical instruments do not possess, urging us to use ancient or forgotten instruments or to invent new ones. Apart from music, research is also needed into instruments and appliances based on special refining and new alloys which can reach a new scale in the octave and produce an unbearably piercing sound or noise.

Lights - Lighting: The lighting equipment currently in use in the theatre is no longer adequate. The particular action of light on the mind comes into play, we must discover oscillating light effects, new ways of diffusing lighting in waves, sheet lighting like a flight of fire-arrows. The colour scale of the equipment currently in use must be revised from start to finish. Fineness, density and opacity factors must be reintroduced into lighting, so as to produce special tonal properties, sensations of heat, cold, anger, fear and so on.

Costume: As to costume, without believing there can be any uniform stage costume that would be the same for all plays, modern dress will be avoided as much as possible not because of a fetishistic superstition for the past, but because it is perfectly obvious certain age-old costumes of ritual intent, although they were once fashionable, retain a revealing beauty and appearance because of their closeness to the traditions which gave rise to them.

The Stage - The Auditorium: We intend to do away with stage and auditorium, replacing them by a kind of single, undivided locale without any partitions of any kind and this will become the very scene of the action. Direct contact will be established between the audience and the show, between actors and audience, from the very fact that the audience is seated in the centre of the action, is encircled and furrowed by it. This encirclement comes from the shape of the house itself.

Abandoning the architecture of present-day theatres, we will rent some kind of barn or hangar rebuilt along lines culminating in the architecture of some churches, holy places, or certain Tibetan temples.

This building will have special interior height and depth dimensions. The auditorium will be enclosed within four walls stripped of any ornament, with the audience seated below, in the middle, on swivelling chairs allowing them to follow the show taking place around them. In effect, the lack of a stage in the normal sense of the word will permit the action to extend itself to the four corners of the auditorium. Special places will be set aside for the actors and action in the four cardinal points of the hall. Scenes will be acted in front of washed walls designed to absorb light. In addition, overhead galleries run right around the circumference of the room as in some Primitive paintings. These galleries will enable actors to pursue one another from one corner of the hall to the other as needed, and the action can extend in all directions at all perspective levels of height and depth. A shout could be transmitted by word of mouth from one end to the other with a succession of amplifications and inflections. The action will unfold, extending its trajectory from floor to floor, from place to place, with sudden outbursts flaring up in different spots like conflagrations. And the show's truly illusive nature will no longer be a hollow gesture any more than will the action's direct, immediate hold on the spectators. For the action, diffused over a vast area, will require the lighting for one scene and the varied lighting for a performance to hold the audience as well as the characters - and physical lighting methods, the thunder and wind whose repercussions will be experienced by the spectators, will correspond with several actions at once, several phases in one action with the characters clinging together like swarms, will endure all the onslaughts of the situations and the external assaults of weather and storms.

However, a central site will be retained which, without acting as a stage properly speaking, enables the body of the action to be concentrated and brought to a climax whenever necessary.

Objects-Masks-Props: Puppets, huge masks, objects of strange proportions appear by the same right as verbal imagery, stressing the physical aspect of all imagery and expression - with the corollary that all objects requiring a stereotyped physical representation will be discarded or disguised.

Decor: No decor. Hieroglyphic characters, ritual costume, thirty foot high effigies of King Lear's beard in the storm, musical instruments as tall as men, objects of unknown form and purpose are enough to fulfil this function.

Topicality: But, you may say, theatre so removed from life, facts or present-day activities... news and events, yes! Anxieties, whatever is profound about them, the prerogative of the few, no! In the Zohar, the story of Rabbi Simeon is as inflammatory as fire, as topical as fire.

Works: We will not act scripted plays but will attempt to stage productions straight from subjects, facts or known works. The type and lay-out of the auditorium itself governs the show as no theme, however vast, is forbidden to us.

Show: We must revive the concept of 'an integral show. The problem is to express it, spatially nourish and furnish it like tap-holes drilled into aflat wall of rock, suddenly generating geysers and bouquets of stone.

The Actor: The actor is both a prime factor, since the show's success depends on the effectiveness of his acting, as well as a kind of neutral, pliant factor since he is rigorously denied any individual initiative. Besides, this is a field where there are no exact rules. And there is a wide margin dividing a man from an instrument, between an actor required to give nothing more than a certain number of sobs and one who has to deliver a speech, using his own powers of persuasion.

Interpretation: The show will be coded from start to finish, like a language. Thus no moves will be wasted, all obeying a rhythm, every character being typified to the nth degree, each gesture, feature and costume to appear as so many shafts of light.

Cinema: Through poetry, theatre contrasts pictures of the unformu-lated with the crude visualization of what exists. Besides, from an action viewpoint, one cannot compare a cinema image, however poetic it may be, since it is restricted by the film, with a theatre image which obeys all life's requirements.

Cruelty: There can be no spectacle without an element of cruelty as the basis of every show. In our present degenerative state, metaphysics must be made to enter the mind through the body. . . .

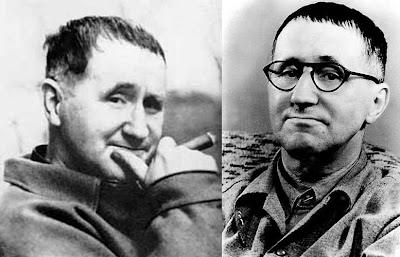

BERTOLT BRECHT (1898-1956)

Theatre for Pleasure or Theatre for Instruction [c. 1936?]

Many people imagine that the term 'epic theatre' is self-contradictory, as the epic and dramatic ways of narrating a story are held, following Aristotle, to be basically distinct. The difference between the two forms was never thought simply to lie in the fact that the one is performed by living beings while the other operates via the written word; epic works such as those of Homer and the medieval singers were at the same time theatrical per¬formances, while dramas like Goethe's Faust and Byron's Manfred are agreed to have been more effective as books. Thus even by Aristotle's definition the difference between the dramatic and epic forms was attributed to their different methods of construction, whose laws were dealt with by two different branches of aesthetics. The method of construction depended on the different way of presenting the work to the public, sometimes via the stage, sometimes through a book; and independently of that there was the 'dramatic element' in epic works and the 'epic element' in dramatic. The bourgeois novel in the last century developed much that was 'dramatic', by which was meant the strong centralization of the story, a momentum that drew the separate parts into a common relationship. A particular passion of utterance, a certain emphasis on the clash of forces are hallmarks of the 'dramatic'. The epic writer Döblin provided an excellent criterion when he said that with an epic work, as opposed to a dramatic, one can as it were take a pair of scissors and cut it into individual pieces, which remain fully capable of life.

This is no place to explain how the opposition of epic and dramatic lost its rigidity after having long been held to be irreconcilable. Let us just point out that the technical advances alone were enough to permit the stage to incorporate an element of narrative in its dramatic productions. The possibility of projections, the greater adaptability of the stage due to mechanization, the film, all completed the theatre's equipment, and did so at a point where the most important transactions between people could no longer be shown simply by personifying the motive forces or subjecting the characters to invisible metaphysical powers.

To make these transactions intelligible the environment in which the people lived had to be brought to bear in a big and 'significant' way.

This environment had of course been shown in the existing drama, but only as seen from the central figure's point of view, and not as an inde¬pendent element. It was defined by the hero's reactions to it. It was seen as a storm can be seen when one sees the ships on a sheet of water unfolding their sails, and the sails filling out. In the epic theatre it was to appear standing on its own.

The stage began to tell a story. The narrator was no longer missing, along with the fourth wall. Not only did the background adopt an attitude to the events on the stage - by big screens recalling other simultaneous events elsewhere, by projecting documents which confirmed or contradicted what the characters said, by concrete and intelligible figures to accompany ab¬stract conversations, by figures and sentences to support mimed transac¬tions whose sense was unclear - but the actors too refrained from going over wholly into their role, remaining detached from the character they were playing and clearly inviting criticism of him.

The spectator was no longer in any way allowed to submit to an experi¬ence uncritically (and without practical consequences) by means of simple empathy with the characters in a play. The production took the subject-matter and the incidents shown and put them through a process of aliena¬tion: the alienation that is necessary to all understanding. When something seems 'the most obvious thing in the world' it means that any attempt to understand the world has been given up.

What is 'natural' must have the force of what is startling. This is the only way to expose the laws of cause and effect. People's activity must simultaneously be so and be capable of being different.

It was all a great change.

The dramatic theatre's spectator says: Yes, I have felt like that too -Just like me - It's only natural - It'll never change - The sufferings of this man appall me, because they are inescapable - That's great art; it all seems the most obvious thing in the world -I weep when they weep, I laugh when they laugh.

The epic theatre's spectator says: I'd never have thought it - That's not the way - That's extraordinary, hardly believable - It's got to stop -The sufferings of this man appall me, because they are unnecessary -That's great art: nothing obvious in it - I laugh when they weep, I weep when they laugh.

THE INSTRUCTIVE THEATRE

The stage began to be instructive.

Oil, inflation, war, social struggles, the family, religion, wheat; the meat market, all became subjects for theatrical representation. Choruses enlightened the spectator about facts unknown to him. Films showed a montage of events from all over the world. Projections added statistical material. And as the 'background' came to the front of the stage so people's activity was subjected to criticism. Right and wrong courses of action were shown. People were shown who knew what they were doing, and others who did not. The theatre became an affair for philosophers, but only for such philosophers as wished not just to explain the world but also to change it. So we had philosophy, and we had instruction. And where was the amuse¬ment in all that? Were they sending us back to school, teaching us to read and write? Were we supposed to pass exams, work for diplomas?

Generally there is felt to be a very sharp distinction between learning and amusing oneself. The first may be useful, but only the second is pleasant. So we have to defend the epic theatre against the suspicion that it is a highly disagreeable, humorless, indeed strenuous affair.

Well: all that can be said is that the contrast between learning and amusing oneself is not laid down by divine rule; it is not one that has always been and must continue to be.

Undoubtedly there is much that is tedious about the kind of learning familiar to us from school, from our professional training, etc. But it must be remembered under what conditions and to what end that takes place.

It is really a commercial transaction. Knowledge is just a commodity. It is acquired in order to be resold. All those who have grown out of going to school have to do their learning virtually in secret, for anyone who admits that he still has something to learn devalues himself as a man whose know¬ledge is inadequate. Moreover the usefulness of learning is very much limited by factors outside the learner's control. There is unemployment, for instance, against which no knowledge can protect one. There is the division of labor, which makes generalized knowledge unnecessary and impossible. Learning is often among the concerns of those whom no amount of concern will get any forwarder. There is not much knowledge that leads to power, but plenty of knowledge to which only power can lead.

Learning has a very different function for different social strata. There are strata who cannot imagine any improvement in conditions: they find the conditions good enough for them. Whatever happens to oil they will benefit from it. And they feel the years beginning to tell. There can't be all that many years more. What is the point of learning a lot now? They have said their final word: a grunt. But there are also strata 'waiting their turn' who are discontented with conditions, have a vast interest in the practical side of learning, want at all costs to find out where they stand, and know that they are lost without learning; these are the best and keenest learners. Similar differences apply to countries and peoples. Thus the pleasure of learning depends on all sorts of things; but none the less there is such a thing as pleasurable learning, cheerful and militant learning.

If there were not such amusement to be had from learning the theatre's whole structure would unfit it for teaching.

Theatre remains theatre even when it is instructive theatre, and in so far as it is good theatre it will amuse.

THEATRE AND KNOWLEDGE

But what has knowledge got to do with art? We know that knowledge can be amusing, but not everything that is amusing belongs in the theatre.

I have often been told, when pointing out the invaluable services that modern knowledge and science, if properly applied, can perform for art and especially for the theatre, that art and knowledge are two estimable but wholly distinct fields of human activity. This is a fearful truism, of course, and it is as well to agree quickly that, like most truisms, it is perfectly true. Art and science work in quite different ways: agreed. But, bad as it may sound, I have to admit that I cannot get along as an artist without the use of one or two sciences. This may well arouse serious doubts as to my artistic capacities. People are used to seeing poets as unique and slightly unnatural beings who reveal with a truly godlike assurance things that other people can only recognize after much sweat and toil. It is naturally dis¬tasteful to have to admit that one does not belong to this select band. All the same, it must be admitted. .

. . In my view the great and complicated things that go on in the world cannot be adequately recognized by people who do not use every possible aid to understanding. . . .

Whatever knowledge is embodied in a piece of poetic writing has to be wholly transmuted into poetry. Its utilization fulfils the very pleasure that the poetic element provokes. If it does not at the same time fulfil that which is fulfilled by the scientific element, none the less in an age of great discoveries and inventions one must have a certain inclination to penetrate deeper into things - a desire to make the world controllable - if one is to be sure of enjoying its poetry.

IS THE EPIC THEATRE SOME KIND OF 'MORAL INSTITUTION'?

According to Friedrich Schiller the theatre is supposed to be a moral institution. In making this demand it hardly occurred to Schiller that by moralizing from the stage he might drive the audience out of the theatre. Audiences had no objection to moralizing in his day. It was only later that Friedrich Nietzsche attacked him for blowing a moral trumpet. To Nietzsche any concern with morality was a depressing affair; to Schiller it seemed thoroughly enjoyable. He knew of nothing that could give greater amusement and satisfaction than the propagation of ideas. The bourgeoisie was setting about forming the ideas of the nation.

Putting one's house in order, patting oneself on the back, submitting one's account, is something highly agreeable. But describing the collapse of one's house, having pains in the back, paying one's account, is indeed a depressing affair, and that was how Friedrich Nietzsche saw things a cen¬tury later. He was poorly disposed towards morality, and thus towards the previous Friedrich too.

The epic theatre was likewise often objected to as moralizing too much. Yet in the epic theatre moral arguments only took second place. Its aim was less to moralize than to observe. That is to say it observed, and then the thick end of the wedge followed: the story's moral. Of course we cannot pretend that we started our observations out of a pure passion for observing and without any more practical motive, only to be completely staggered by their results. Undoubtedly there were some painful discrepancies in our environment, circumstances that were barely tolerable, and this not merely on account of moral considerations. It is not only moral considerations that make hunger, cold and oppression hard to bear. Similarly the object of our inquiries was not just to arouse moral objections to such circum¬stances (even though they could easily be felt - though not by all the audience alike; such objections were seldom for instance felt by those who profited by the circumstances in question) but to discover means for their elimination. We were not in fact speaking in the name of morality but in that of the victims. These truly are two distinct matters, for the victims are often told that they ought to be contented with their lot, for moral reasons. Moralists of this sort see man as existing for morality, not morality for man. At least it should be possible to gather from the above to what degree and in what sense the epic theatre is a moral institution. . . .

[Epic theatre] demands not only a certain technological level but a powerful move¬ment in society which is interested to see vital questions freely aired with a view to their solution, and can defend this interest against every contrary trend.

The epic theatre is the broadest and most far-reaching attempt at large-scale modern theatre, and it has all those immense difficulties to overcome that always confront the vital forces in the sphere of politics, philosophy, science and art.

From The Epic Theatre [1930]

The modern theatre is the epic theatre. The following table shows certain changes of emphasis as between the dramatic and the epic theatre:

EPIC THEATRE

Narrative

turns the spectator into an observer, but

arouses his capacity for action

forces him to take decisions

the spectator stands outside, studies

the human being is the object of the inquiry

he is alterable and able to alter

each scene for itself

montage

in curves

jumps

man as a process

social being determines thought

reason

DRAMATIC THEATRE

implicates the spectator in a stage

situation

wears down his capacity for action

provides him with sensations

the spectator is in the thick of it, shares the experience

the human being is taken

for granted

he is unalterable

one scene makes another

growth

linear development

evolutionary determinism

man as a fixed point

thought determines being

feeling

Wednesday, November 5, 2008

Aristotle on Tragedy

The rediscovery of Aristotle’s works in the west (through contact with the Muslim world) was one of the primary factors in the revival of learning that led to the Renaissance. His writings on science inspired a turn to empiricism and direct observation of the material world. His remarks on tragedy in the Poetics served as the foundation of the classical aesthetic that European writers sought to fulfill from roughly the 15th-18th centuries (although it’s not likely that Shakespeare concerned himself with it). The feature of Aristotle’s definition of tragedy that is most often still cited is his thesis about its function: that by arousing conflicting feelings of fear and pity, tragedy allows the audience to achieve catharsis of strong and possibly destructive emotions. (I have italicized especially important phrases.)

From Part IV

Poetry in general seems to have sprung from two causes, each of them lying deep in our nature. First, the instinct of imitation is implanted in man from childhood, one difference between him and other animals being that he is the most imitative of living creatures, and through imitation learns his earliest lessons; and no less universal is the pleasure felt in things imitated. We have evidence of this in the facts of experience. Objects which in themselves we view with pain, we delight to contemplate when reproduced with minute fidelity: such as the forms of the most ignoble animals and of dead bodies. The cause of this again is, that to learn gives the liveliest pleasure, not only to philosophers but to men in general; whose capacity, however, of learning is more limited. Thus the reason why men enjoy seeing a likeness is, that in contemplating it they find themselves learning or inferring, and saying perhaps, 'Ah, that is he.' For if you happen not to have seen the original, the pleasure will be due not to the imitation as such, but to the execution, the coloring, or some such other cause.

Imitation, then, is one instinct of our nature. Next, there is the instinct for 'harmony' and rhythm, meters being manifestly sections of rhythm. Persons, therefore, starting with this natural gift developed by degrees their special aptitudes, till their rude improvisations gave birth to Poetry.

Poetry now diverged in two directions, according to the individual character of the writers. The graver spirits imitated noble actions, and the actions of good men. The more trivial sort imitated the actions of meaner persons, at first composing satires, as the former did hymns to the gods and the praises of famous men. . . . Tragedy- as also Comedy- was at first mere improvisation. The one originated with the authors of the Dithyramb, the other with those of the phallic songs, which are still in use in many of our cities. Tragedy advanced by slow degrees; each new element that showed itself was in turn developed. Having passed through many changes, it found its natural form, and there it stopped.

Aeschylus first introduced a second actor; he diminished the importance of the Chorus, and assigned the leading part to the dialogue. Sophocles raised the number of actors to three, and added scene-painting. Moreover, it was not till late that the short plot was discarded for one of greater compass, and the grotesque diction of the earlier satyric form for the stately manner of Tragedy. The iambic measure then replaced the trochaic tetrameter, which was originally employed when the poetry was of the satyric order, and had greater with dancing. Once dialogue had come in, Nature herself discovered the appropriate measure. For the iambic is, of all measures, the most colloquial we see it in the fact that conversational speech runs into iambic lines more frequently than into any other kind of verse . . .

From Part VI

. . . Let us now discuss Tragedy, resuming its formal definition, as resulting from what has been already said.

Tragedy, then, is an imitation of an action that is serious, complete, and of a certain magnitude; in language embellished with each kind of artistic ornament, the several kinds being found in separate parts of the play; in the form of action, not of narrative; through pity and fear effecting the proper purgation of these emotions. . . .

Now as tragic imitation implies persons acting, it necessarily follows in the first place, that Spectacular equipment will be a part of Tragedy. Next, Song and Diction, for these are the media of imitation. By 'Diction' I mean the mere metrical arrangement of the words: as for 'Song,' it is a term whose sense every one understands.

Again, Tragedy is the imitation of an action; and an action implies personal agents, who necessarily possess certain distinctive qualities both of character and thought; for it is by these that we qualify actions themselves, and these- thought and character- are the two natural causes from which actions spring, and on actions again all success or failure depends. Hence, the Plot is the imitation of the action- for by plot I here mean the arrangement of the incidents. By Character I mean that in virtue of which we ascribe certain qualities to the agents. Thought is required wherever a statement is proved, or, it may be, a general truth enunciated. Every Tragedy, therefore, must have six parts, which parts determine its quality- namely, Plot, Character, Diction, Thought, Spectacle, Song. . . .

But most important of all is the structure of the incidents. For Tragedy is an imitation, not of men, but of an action and of life, and life consists in action, and its end is a mode of action . . . Now character determines men's qualities, but it is by their actions that they are happy or the reverse. Dramatic action, therefore, is not with a view to the representation of character: character comes in as subsidiary to the actions. Hence the incidents and the plot are the end of a tragedy; and the end is the chief thing of all.. . . . Again, if you string together a set of speeches expressive of character, and well finished in point of diction and thought, you will not produce the essential tragic effect nearly so well as with a play which, however deficient in these respects, yet has a plot and artistically constructed incidents. Besides which, the most powerful elements of emotional interest in Tragedy- Peripeteia or Reversal of the Situation, and Recognition scenes- are parts of the plot. . . .

The plot, then, is the first principle, and, as it were, the soul of a tragedy; Character holds the second place. A similar fact is seen in painting. The most beautiful colors, laid on confusedly, will not give as much pleasure as the chalk outline of a portrait. Thus Tragedy is the imitation of an action, and of the agents mainly with a view to the action.

Friday, October 31, 2008

From Perez Hilton

The tenth face of England's Dr. Who, David

Tennant , is bowing out of the show after five years with the wildly successful and highly esteemed sciencefiction drama.He will appear in the Christmas episode and 4 hour long specials to air in 2009 and 2010. But after that, it will be time for someone new to take on the role of the shape-shifting time-traveling alien.

Tennant said of his departure, "This show has been so special to me. I don't want to outstay my welcome."

Tennant, who is a classically trained actor, is now starring as Hamlet for the Royal Shakespeare Company's production of Shakespeare's famous play.

http://perezhilton.com/2008-10-30-david-tennant-is-leaving-dr-who

Sunday, October 26, 2008

Saturday, October 25, 2008

Wednesday, October 22, 2008

Aeschylus: Agamemnon (1983 TV) part 9/10

The Peter Hall version at the National Theatre of Great Britain.

The doors to the palace open, revealing Agamemnon's corpse. Clytemnestra exults.

Aeschylus: Agamemnon (1983 TV) part 8/10

The Peter Hall version at the National Theatre of Great Britain.

The deaths of Agamenon and Cassandra.

Aeschylus: Agamemnon (1983 TV) part 7/10

The Peter Hall version at the National Theatre of Great Britain.

Agamemnon steps on the purple carpet and seals his fate. Cassandra prophesies.

Tuesday, October 21, 2008

Saxo Grammaticus - The Story of Amleth from the Gesta Danorum, c. 12th century

No one really knows what Shakespeare’s sources for Hamlet were. He is not likely to have consulted Saxo’s Gesta Danorum, but it was the source for a story in Belleforest’s Histoires Tragiques, which he may have known. Some elements of the story are common folktale themes: The wicked stepfather wh is revealed as the father’s murderer; the hero who disguises himself as a fool, biding his time until he can reclaim his rights; the alteration in a letter that condemns the messengers to death. Saxo’s Amleth also kills the spy who eavesdrops on his conversation with his mother, and reappears at his own funeral (rather than another character’s). One very important motif does not appear in Saxo: the appearance of the hero’s father’s ghost. It probably derives from the so-called Ur-Hamlet—an earlier play by another playwright.

Horwendil, King of Denmark, married Gurutha, the daughter of Rorik, and she bore him a son, whom they named Amleth. Horwendil's good fortune stung his brother Feng with jealousy, so that the latter resolved treacherously to waylay his brother, thus showing that goodness is not safe even from those of a man's own house. And behold when a chance came to murder him, his bloody hand sated the deadly passion of his soul.

Then he took the wife of the brother he had butchered, capping unnatural murder with incest. For whoso yields to one iniquity, speedily falls an easier victim to the next, the first being an incentive to the second. Also the man veiled the monstrosity of his deed with such hardihood of cunning, that he made up a mock pretense of goodwill to excuse his crime, and glossed over fratricide with a show of righteousness. Gerutha, said he, though so gentle that she would do no man the slightest hurt, had been visited with her husband's extremest hate; and it was all to save her that he had slain his brother; for he thought it shameful that a lady so meek and unrancorous should suffer the heavy disdain of he husband. Nor did his smooth words fail in their intent; for at courts, where fools are sometimes favored and backbiters preferred, a lie lacks not credit. Nor did Feng keep from shameful embraces the hands that had slain a brother; pursuing with equal guilt both of his wicked and impious deeds.

Amleth beheld all this, but feared lest too shrewd a behavior might make his uncle suspect him. So he chose to feign dullness, and pretend an utter lack of wits. This cunning course not only concealed his intelligence but ensured his safety.

Every day he remained in his mother's house utterly listless and unclean, flinging himself on the ground and bespattering his person with foul and filthy dirt. His discolored face and visage smudged with slime denoted foolish and grotesque madness. All he said was of a piece with these follies; all he did savored of utter lethargy.

He used at times to sit over the fire, and, raking up the embers with his hands, to fashion wooden crooks, and harden them in the fire, shaping at their tips certain barbs, to make them hold more tightly to their fastenings. When asked what he was about, he said that he was preparing sharp javelins to avenge his father. This answer was not a little scoffed at, all men deriding his idle and ridiculous pursuit; but the thing helped his purpose afterwards. Now istwas his craft in this matter that first awakened in the deeper observers a suspicion of his cunning. For his skill in a trifling art betokened the hidden talent of the craftsman; nor could they believe the spirit dull where the hand had acquired so cunning a workmanship. Lastly, he always watched with the most punctual care over his pile of stakes that he had pointed in the fire. Some people, therefore, declared that his mind was quick enough, and fancied that he only played the simpleton in order to hide his understanding, and veiled some deep purpose under a cunning feint.

His wiliness (said these) would be most readily detected, if a fair woman were put in his way in some secluded place, who would provoke his mind to the temptations of love; all man's natural temper being too blindly amorous to be artfully dissembled, and this passion being also too impetuous to be checked by cunning. Therefore, if his lethargy were feigned, he would seize the opportunity, and yield straightway to violent delights. Some men were commissioned to draw the young man in his rides into a remote part of the forest, and there assail him with a temptation of this nature. Among these chanced to be a foster-brother of Amleth, who had not ceased to have regard to their common nurture; and who esteemed his present orders less than the memory of their past fellowship. He attended Amleth among his appointed train, being anxious not to entrap, but to warn him; and was persuaded that he would suffer the worst if he showed the slightest glimpse of sound reason, and above all if he did the act of love openly. This was also plain enough to Amleth himself. For when he was bidden mount his horse, he deliberately set himself in such a fashion that he turned his back to the neck and faced about, fronting the tail; which he proceeded to encompass with the reins, just as if on that side he would check the horse in its furious pace. By this cunning thought he eluded the trick, and overcame the treachery of his uncle. The reinless steed galloping on, with the rider directing its tail, was ludicrous enough to behold. . . .

Then they purposely left him, that he might pluck up more courage to practice wantonness. The woman whom his uncle had dispatched met him in a dark spot, as though she had crossed him by chance; and he took her and would have ravished her, had not his foster-brother, by a secret device, given him an inkling of the trap. . . . Alarmed, scenting a trap, and fain to possess his desire in greater safety, he caught up the woman in his arms and dragged her off to a distant and impenetrable fen. Moreover, when they had lain together, he conjured her earnestly to disclose the matter to none, and the promise of silence was accorded as heartily as it was asked. For both of them had been under the same fostering in their childhood; and this early rearing in common had brought Amleth and the girl into great intimacy.

So, when he had returned home, they all jeeringly asked him whether he had given way to love, and he avowed that he had ravished the maid. The answer was greeted with shouts of merriment from the bystanders. The maiden, too, when questioned on the matter, declared that he had done no such thing; and her denial was the more readily credited when it was found that the escort had not witnessed the deed.,Thus all were worsted, and none could open the secret lock of the young man's wisdom.

But a friend of Feng, gifted more with assurance than judgment, declared that the unfathomable cunning of such a mind could not be detected by any vulgar plot, for the man's obstinacy was so great that it ought not to be assailed with any mild measures; there were many sides to his wiliness, and it ought not to be entrapped by any one method. Accordingly, said he, his own profounder acuteness had hit on a more delicate way, which was well fitted to be put in practice, and would effectually discover what they desired to know. Feng was purposely to absent himself, pretending affairs of great import. Amleth should be closeted alone with his mother in her chamber; but a man should first be commissioned to place himself in a concealed part of the room and listen heedfully to what they talked about. For if the son had any wits at all he would not hesitate to speak out in the hearing of his mother, or fear to trust himself to the fidelity of her who bore him. The speaker, loath to seem readier to devise than to carry out the plot, zealously proffered himself as the agent of the eavesdropping. Feng rejoiced at the scheme, and departed on pretense of a long journey. Now he who had given up this counsel repaired privily to the room where Amleth was shut up with his mother, and lay down skulking in the straw.

But Amleth had his antidote for the treachery. Afraid of being overheard by some eavesdropper, he at first resorted to his usual imbecile ways, and crowed like a noisy cock, beating his arms together to mimic the flapping of wings. Then he mounted the straw and began to swing his body and jump again and again, wishing to try if aught lurked there in hiding. Feeling a lump beneath his feet, he drove his sword into the spot, and impaled him who lay hid. Then he dragged him from his concealment and slew him. Then, cutting his body into morsels, he seethed it in boiling water, and flung it through the mouth of an open sewer for the swine to eat, bestrewing the stinking mire with his hapless limbs.

Having in this wise eluded the snare, he went back to the room. Then his mother set up a great wailing and began to lament her son's folly to his face; but he said: "Most infamous of women! dost thou seek with such lying lamentations to hide thy most heavy guilt? Wantoning like a harlot, thou hast entered a wicked and abominable state of wedlock, embracing with incestuous bosom thy husband's slayer, and wheedling with filthy lures of blandishment him who had slain the father of thy son. This, forsooth, is the way that the mares couple with the vanquishers of their mates; for brute beasts are naturally incited to pair indiscriminately; and it would seem that thou, like them, hast clean forgot thy first husband. As for me, not idly do I wear the mask of folly; for I doubt not that he who destroyed his brother will riot as ruthlessly in the blood of his kindred. Therefore it is better to choose the garb of dullness than that of sense, and to borrow some protection from a show of utter frenzy. Yet the passion to avenge my father still burns in my heart; but I am watching the chances, I await the fitting hour. There is a place for all things; against so merciless and dark a spirit must be used the deeper devices of the mind. And thou, who hadst been better employed in lamenting thine own disgrace, know it is superfluity to bewail my witlessness; thou shouldst weep for the blemish in thine own mind, not for that in another's. On the rest see thou keep silence." With such reproaches he rent the heart of his mother and redeemed her to walk in the ways of virtue, teaching her to set the fires of the past above the seductions of the present.

Feng now suspected that his stepson was certainly full of guile, and desired to do away with him, but durst not do the deed for fear of the displeasure, not only of Amleth's grandsire Rorik, but also of his own wife. So he thought that the King of Britain should be employed to slay him, so that another could do the deed, and he be able to feign innocence. Thus, desirous to hide his cruelty, he chose rather to besmirch his friend than to bring disgrace on his own head. Amleth, on departing, gave secret orders to his mother to hang the hall with knotted tapestry, and to perform pretended obsequies for him a year thence; promising that he would then return. Two retainers of Feng then accompanied him, bearing a letter graven on wood--a kind of letter enjoined the king of the Britons to put to death the youth who was sent over to him.

While they were reposing, Amleth searched their coffers, found the letter, and read the instructions therein. Whereupon he erased all the writing on the surface, substituted fresh characters, and so, changing the purport of the instructions, shifted his own doom upon his companions. Nor was he satisfied with removing from himself the sentence of death and passing the peril on to others, but added and entreaty that the King of Britain would grant his daughter in marriage to a youth of great judgment whom he was sending to him. Under this was falsely marked the signature of Feng.

Now when they had reached Britain, the envoys went to the king, and proffered him the letter which they supposed was an implement of destruction to one another, but which really betokened death to themselves. The king dissembled the truth, and entreated them hospitably and kindly. Then Amleth scouted all the splendor of the royal banquet like vulgar viands, and abstaining very strangely, rejected that plenteous feast, refraining from the drink even as from the banquet. All marveled that a youth and a foreigner should disdain the carefully-cooked dainties of the royal board and the luxurious banquet provided, as if it were some peasant's relish. So, when the revel broke up, and the king was dismissing his friends to rest, he had a man sent into the sleeping-room to listen secretly, in order that he might hear the midnight conversation of his guests.

[The King of Britain learns that Amleth’s riddling answers to his companions actually display acute discernment.] Then the king adored the wisdom of Amleth as though it were inspired, and gave him his daughter to wife; accepting his bare word as though it were a witness from the skies. Moreover, in order to fulfill the bidding of his friend, he hanged Amleth's companions on the morrow. Amleth, feigning offense, treated this piece of kindness as a grievance, and received from the king, as compensation, some gold, which he afterwards melted in the fire, and secretly caused to be poured into some hollowed sticks.

When he had passed a whole year with the king he obtained to make a journey, and returned to his own land, carrying away of all his princely wealth and state only the sticks which held the gold.

On reaching Jutland, he exchanged his present attire for his ancient demeanor, which he had adopted for righteous ends, purposely assuming an aspect of absurdity. Covered with filth, he entered the banquet-room where is own obsequies were being held, and struck all men utterly aghast, rumor having falsely noised abroad his death. At last terror melted into mirth, and the guests jeered and taunted one another, that he whose last rites they were celebrating as though he were dead, should appear in the flesh.

When he was asked concerning his comrades, he pointed to the sticks he was carrying, and said, "Here is both the one and the other." This he observed with equal truth and pleasantry; for his speech, though most thought it idle, yet departed not from the truth; for it pointed at the weregild of the slain as though it were themselves. Thereon, wishing to bring the company into a gayer mood, he joined the cupbearers, and diligently did the office of plying the drink.

Then, to prevent his loose dress hampering his walk, he girded his sword upon his side, and purposely drawing it several times, pricked his fingers with its point. The bystanders accordingly had both sword and scabbard riveted across with an iron nail.

Then, to smooth the way more safely to his plot, he went to the lords and plied them heavily with draught upon draught, and drenched them all so deep in wine, that their feet were made feeble with drunkenness, and they turned to rest within the palace, making their bed where they had reveled. Then he saw they were in a fit state for his plots, and thought that here was a chance offered to do his purpose. So he took out of his bosom the stakes he had long ago prepared, and went into the building, where the ground lay covered with the bodies of the nobles wheezing off their sleep and their debauch. Then, cutting away its supports, he brought down the hanging his mother had knitted, which covered the inner as well as the outer walls of the hall. This he flung upon the snorers, and then applying the crooked stakes, he knotted and bound them up in such insoluble intricacy, that not one of the men beneath, however hard he might struggle, could contrive to rise.

After this he set fire to the palace. The flames spread, scattering the conflagration far and wide. It enveloped the whole dwelling, destroyed the palace, and burnt them all while they were either buried in deep sleep of vainly striving to arise. Then he went to the chamber of Feng, who had before this been conducted by his train into his pavilion; plucked up a sword that chanced to be hanging to the bed, and planted his own in its place. Then, awakening his uncle, he told him that his nobles were perishing in the flames, and that Amleth was here, armed with his old crooks to help him, and thirsting to exact the vengeance, now long overdue, for his father's murder. Feng, on hearing this, leapt from his couch, but was cut down while, deprived of his own sword, he strove in vain to draw the strange one.

O valiant Amleth, and worthy of immortal fame, who being shrewdly armed with a feint of folly, covered a wisdom too high for human wit under a marvelous disguise of silliness! and not only found in his subtlety means to protect his own safety, but also by its guidance found opportunity to avenge his father. By this skillful defense of himself, and strenuous revenge for his parent, he has left it doubtful whether we are to think more of his wit or his bravery.

[Amleth inherits the throne and rules with wisdom.]

Wednesday, October 15, 2008

Violent Ending to the story

I found this on YouTube. Ridiculous, stupid, and inaccurate. Slightly funny though

Saturday, October 11, 2008

Sir Francis Bacon - Of Revenge

Francis Bacon – Of Revenge (1625)

Sir Francis Bacon is one of the most important intellectual figures of the English Renaissance, an advisor to both Queen Elizabeth I and James I--and indeed one of the most notable instances of an eminent philosopher taking an active part in public and political affairs, and as such, was significantly responsible for England's exploration of America. He is considered one of the founders of the modern scientific method and of empiricism--the view that intellectual matters should be decided based upon observation and experimentation upon the actual, physical world, and not on the authority of the ancients, or of logic and reasoning alone.

Bacon's relation to Shakespeare has long been discussed. It appears that he was a fan and advocate of Shakespeare and his company. But in the 19th century, he became the first of a long list of the playwright's contemporaries to be proposed as the "real" author of the plays known as Shakespeare's. It should be remembered that the originator of the theory was Delia Bacon, apparently seizing on a coincidence of names, who later went mad.

REVENGE is a kind of wild justice; which the more man's nature runs to, the more ought law to weed it out. For as for the first wrong, it doth but offend the law; but the revenge of that wrong pulleth the law out of office. Certainly, in taking revenge, a man is but even with his enemy; but in passing it over, he is superior; for it is a prince's part to pardon. And Salomon, I am sure, saith, It is the glory of a man to pass by an offence.

That which is past is gone, and irrevocable; and wise men have enough to do with things present and to come: therefore they do but trifle with themselves, that labour in past matters.

There is no man doth a wrong for the wrong's sake; but thereby to purchase himself profit, or pleasure, or honour, or the like. There why should I be angry with a man for loving himself better than me? And if any man should do wrong merely out of ill nature, why, yet it is but like the thorn or briar, which prick and scratch, because they can do no other.

The most tolerable sort of revenge is for those wrongs which there is no law or remedy; but then let a man take heed the revenge be such as there is no law to punish; else a man's enemy is still beforehand, and it is two for one.

Some, when they take revenge, are desirous the party should know whence it cometh: this is the more generous. For the delight seemeth to be not so much in doing the hurt as in making the party repent: but base and crafty cowards are like the arrow that flieth in the dark.

Cosmus, Duke of Florence, had a desperate saying against perfidious or neglecting friends, as if those wrongs were unpardonable: You shall read (saith he) that we are commanded to forgive our friends. But yet the spirit of Job was in a better tune: Shall we (saith he) take good at God's hands, and not be content to take evil also? And so of friends in a proportion.

This is certain, that a man that studieth revenge keeps his own wounds green, which otherwise would heal and do well.

Public revenges are for the most part fortunate; as that for the death of Caesar; for the death of Pertinax(1); for the death of Henry the Third of France (2); and many more. But in private revenges it is not so. Nay rather, vindictive persons live the life of witches; who as they are mischievous, so end they unfortunate.

(1) Publius Helvius Pertinax became emperor of Rome in 193 and was assassinated three months after his accession to the throne by a soldier in his praetorian Guard.

(2) King of France, 1574-1589, assassinated during the Siege of Paris.

Natalie Dessay - Hamlet -

Here is a serious performance of the first part of Ophelia's aria from Thomas' Hamlet--the one Lunita found a parody of. You can find the other two parts by searching Natalie Dessay Hamlet (or Ophelia) at YouTube.